Lyft is going public, and it’s losing money while doing so. It’s not alone in being unprofitable, however. Uber, its chief rival, also loses money. The ride-hailing sector as a whole has posted blistering growth and scarce profits.

Subscribe to the Crunchbase Daily

But now that Lyft has filed to go public, we can better understand why it loses money, and how it accounts for promotions and discounts in its results.1

Last October, we explored why Uber loses money, stacking its cost structure compared to its gross profit (head here for definitions and help). We’ll repeat the exercise with Lyft, and then dig into the details a bit more.

For a broader look into Lyft’s IPO filing, head here. Let’s get started.

Big Picture

Much like Uber, Lyft loses money because it spends more money than it brings in.

More specifically, Lyft’s operating costs are far higher than its gross profit. What does that mean? It means that the amount of money left over after you deduct costs of revenue from Lyft’s top line (top line is financial slang for revenue) isn’t enough to cover what the company spends to operate. So, Lyft runs at a deficit and has done so in every quarter reported in its S-1 filing.

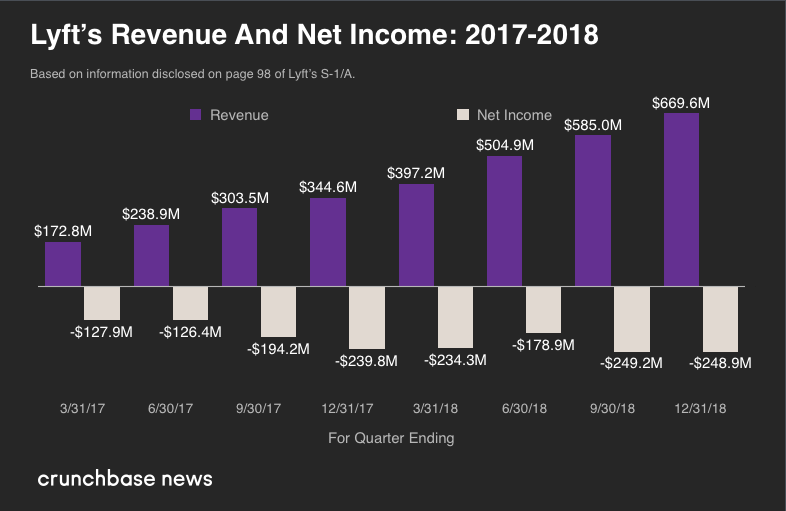

Here’s what that looks like:

Putting the company’s results into perspective, in calendar 2018 Lyft generated revenue of $2.16 billion. However, that figure came with costs of revenue totaling $1.24 billion, leaving $913.2 million in gross profit with which Lyft could use to cover its operating costs. However, Lyft’s “operations and support,” “research and development,” “sales and marketing,” and “general and administrative” costs were larger than that gross profit.

Summed together, Lyft’s operating costs (not including costs of revenue) came to $1.89 billion in 2018. That’s about double the company’s gross profit in the same time period. So we can surmise that Lyft lost around $900 million in the year. The real figure was $911.3 million, inclusive of income taxes.

Losses From Two Perspectives

There are two ways to think about losses. First, loss in absolute terms. And second, loss in relative terms.

Lyft’s absolute losses (net losses, in this case) are growing. Lyft lost $911.3 million in 2018, up from $688.3 million in 2017, and $682.8 million in 2016. The company also lost just under $500 million in the final two quarters of 2018, the two most unprofitable three-month periods detailed in its S-1 filing.

At the same time, Lyft’s net loss as a percent of revenue (a relative calculation) shows dramatic improvement over the same time periods. Lyft’s net loss came to 198.9 percent of revenue in 2016. That figure fell to 64.9 percent in 2017, and 45.3 percent in 2018.

You can look at the company’s net losses therefore from two key perspectives, that they are large and growing, or that they are falling as a percent of revenue as Lyft scales. It’s up for investors to determine which perspective matters more. The bullish case may focus on how losses are falling as a percent of revenue; the bearish cash could fixate on the rising losses in dollar terms.

But there’s quite a lot baked into Lyft’s figures that we need to understand, so let’s unpack a key ride-hailing class of expenses.

Discounts And Incentives

Lyft runs a two-sided marketplace. That’s a tough place to be, as the company has to ensure there’s enough demand (riders), and supply (drivers). There are two ways to account for the tools Lyft uses to balance its marketplace (discounts, promotions and incentives): revenue reductions, or sales and marketing costs.

Efforts that are accounted as revenue reductions are sometimes called “contra-revenue” items, costs that you deduct against revenue, lowering top-line results.

In contrast, some marketplace balancing efforts are categorized as sales and marketing costs, thus appearing on that particular line item in the company’s income statement. These costs, however, do not lower revenue. Instead, they are operating costs that lower profitability and operating margins.

Got all that? Good. Let’s explore how Lyft accounts for particular promotions and discounts. Here’s how Lyft describes its two-sided marketplace and its work to balance it in its S-1:

To ensure that a sufficient number of drivers are available to provide rides during peak demand hours, we utilize a range of incentives for drivers, which have the effect of reducing our revenue. To increase the number of rides that riders take through our platform, we often engage in promotions to riders, which, depending on the type of promotion, are treated either as a reduction to revenue or a sales and marketing expense.

From the above paragraph, we can tell that Lyft’s driver incentives tend to be contra-revenue. At the same time, we can see that rider-facing demand generation tends to be a sales and marketing cost.

I was curious if Lyft puts any similar expenses into its cost of revenue line item, but its S-1 indicates that it doesn’t:

Cost of revenue primarily consists of insurance costs that are generally required under TNC and city regulations for ridesharing and Light Vehicle rentals, respectively, payment processing charges, including merchant fees and chargebacks, hosting and platform-related technology costs, amortization of technology related intangible assets, certain direct costs related to Light Vehicles and the Select Express Drive Partner program and personnel-related compensation costs.

That settled, what falls under Lyft’s “sales and marketing” bucket when it comes to demand generation?

Sales and marketing expenses primarily consist of advertising expenses, rider incentives and refunds, personnel-related compensation costs and driver incentives for referring new drivers or riders. Sales and marketing costs are expensed as incurred.

So, those items are likely key drivers of Lyft’s rising sales and marketing spend, which grew from $434.3 million in 2016 to $567.0 million in 2017 to $803.8 million in 2018.

The figures will continue to rise, at least according to Lyft:

We plan to continue to invest in sales and marketing to attract and retain drivers and riders on our platform and increase our brand awareness. We expect that sales and marketing expenses will increase in absolute dollars in future periods and vary from period-to-period as a percentage of revenue in the near-term. We expect that, in the long-term, our sales and marketing expenses will decrease as a percentage of revenue as we continue to drive efficiencies by reducing rider acquisition expenses and the use of rider incentives.

Summing

So, Lyft loses money because it’s revenue doesn’t generate enough gross profit to cover its operating expenses. Looking deeper into the figures, Lyft mostly counts driver incentives against revenue, and mostly counts rider incentives as a sales and marketing cost. The two have the impact, then, of cutting Lyft’s top line, and accentuating its cost structure, helping build out its unprofitability.

Taken as a whole, that’s why Lyft loses money.

Illustration: Li-Anne Dias.

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration showing AI agents, depicted by robots, performing digital tasks. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Quarterly-agenticAI-latin-america-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration showing AI agents, depicted by robots, performing digital tasks. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Quarterly-agenticAI-asia-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers