MicroAcquire founder Andrew Gazdecki grew his first company to $10 million in revenue before selling it to a private equity firm for a “small eight-figure exit.” Venture capitalists wouldn’t have been happy with an exit like that, Gazdecki said, but he was satisfied.

“The benefits of bootstrapping is like being at the blackjack table where you have a lot of chips and you can cash in whenever you want,” Gazdecki said. “You don’t need board approval. You can sell for $30 million. That’s a fire sale for a venture firm.”

Gazdecki is one founder who raised venture funding after bootstrapping—running a company without outside funding—for a year. Crunchbase data shows that more than 1,000 startups founded before 2015 raised a pre-seed or seed round in 2021, meaning they operated without venture capital or with minimal funding for several years before raising money from VCs or angel investors.

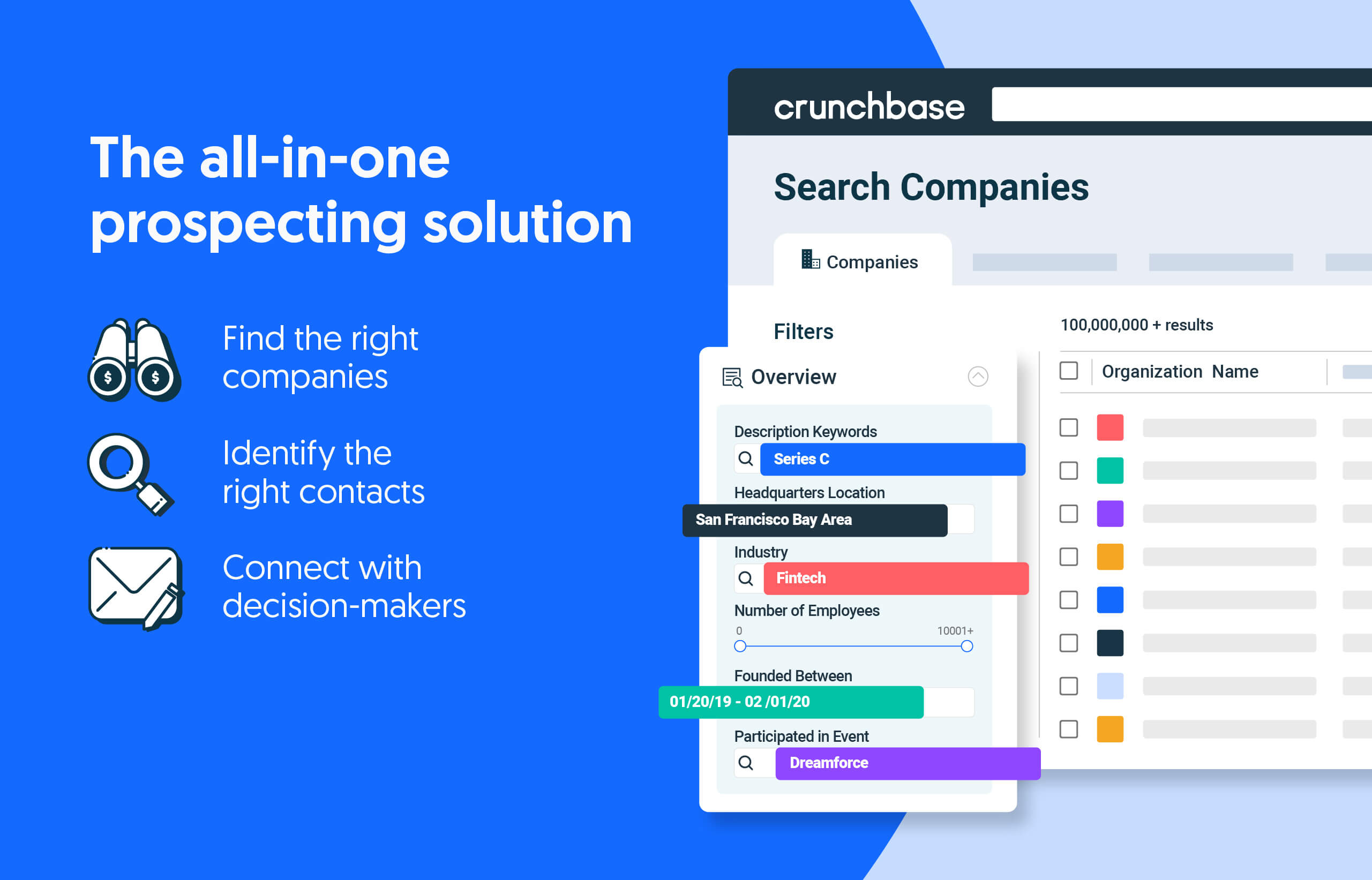

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Despite bootstrapped companies not fitting into the traditional Silicon Valley mold, some VCs are looking to invest in these companies, according to Kurt Beyer, a lecturer in entrepreneurship and innovation at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

That’s for a few reasons.

“One, they may have gotten through the ‘valley of death’ already, they may have achieved product-market fit, may have some revenue, so in a way they have de-risked the startup,” Beyer said. “If I make an investment as a VC during the valley of death, pre-revenue, there’s a tremendous amount of risk.”

Before venture capital became the industry it is today, all startups were bootstrapped, Beyer said. One of the benefits of the VC industry forming around the 1960s was “we could be much more aggressive and create startups around much more expensive types of products and services,” he said. “The perfect example of that is capital-intensive companies, like Tesla.”

Companies in areas such as biotech and medical devices are almost forced to take the VC route because it takes so long to generate revenue. The so-called valley of death—the period without revenue—for such companies is so deep and so long that VC is basically the only way for those types of companies to survive.

But there are many other types of startups that can grow organically, and technology services like Amazon’s AWS make it easier to bootstrap, Beyer said. A startup wanting to build an app, for example, doesn’t have to raise VC money to build its own servers.

“That means in certain consumer-facing (companies), apps, or pieces of software, the valley of death is very shallow now, prior to revenue,” Beyer said. “So it is possible to get through, maybe through friends and family, and then organically grow it, especially if you can get to revenue relatively quickly and the margins are high.”

Skin in the game

Bootstrapping also shows that the company has some staying power, Beyer said.

“This is a team that was able to execute and get through the valley of death on a minimum budget, they were very efficient, they made good decisions around cost, that’s all interesting also,” Beyer said. “That’s a very good signal for a VC firm. But again, that can only happen with certain products and services. There’s no way that certain classifications of products and services even have the option to bootstrap.”

Accel is an example of a VC firm that’s been keen on investing in bootstrapped companies. Over the last 13 years, the firm has invested in around 35 bootstrapped or lightly capitalized businesses, according to the firm. Among its notable investments are Utah-based Qualtrics, which raised a Series A co-led by Accel in 2012, and Australia-based Atlassian, which the firm invested in as early as 2010, per Crunchbase.

With record amounts of venture capital being invested globally, investors are also finding themselves competing fiercely with other VCs to deploy capital and back the most promising startups. That could prompt more venture firms to pursue companies that may not fit the typical startup mold.

Accel always had a global mentality and thought of Silicon Valley not as a place, but a state of mind, General Partner Rich Wong said. Around 12 to 15 years ago—long before the pandemic made remote work more mainstream—the firm’s leadership started to believe that great tech companies wouldn’t all necessarily hail from wealthy coastal areas like Boston or the Bay Area.

“Back 10, 15 years ago, many first believed you had to have the company in Silicon Valley,” Wong said. “There was a lot of chatter that if you found founders in Romania, Finland you would require them to come to the Bay Area to get funding,” he said.

Accel, however, established global offices in places like London, Israel and India, and that exposed them to world-class entrepreneurs, said partner Arun Mathew.

There are a few common qualities that make bootstrapped companies a good investment, according to Mathew.

First, when a company is based outside of a place like the Bay Area, which has a large and established tech ecosystem, it has to work a bit harder to get technical talent.

At the same time, capital constraints when a company’s trying to find product-market fit without outside funding to tide it over can be a good thing, Mathew said. Without venture dollars for a boost, bootstrapped companies are hyper-focused on creating a healthy business, building a product that people love, and generating a profit, which creates a sense of discipline.

“We really like the formation story of these companies where they don’t raise much capital, they end up finding product-market fit, they end up infusing their DNA with a sense of discipline that sort of carries throughout,” he said.

But taking venture dollars isn’t without its challenges. Bootstrapped companies aren’t often used to a Silicon Valley style of running a business, Wong said. For example, many bootstrapped companies haven’t done GAAP financial accounting or dealt with options or equity. Because of that, VCs who invest in bootstrapped companies can’t be passive investors.

To bootstrap or not?

While raising venture capital is one way to build a business, it’s not the only way. There are some key benefits that come with bootstrapping, according to Gazdecki.

“If you want to get rich, you should bootstrap, and if you want to disrupt a market, you should raise venture capital,” he said.

When a founder bootstraps their company, they own the whole entity. They can then sell the company whenever they want without board approval or people to answer to.

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Companies that decide to take on venture funding after bootstrapping for some time often do so because either the founder’s personal ambition changes or the market size changes, Gazdecki said.

In the case of MicroAcquire, Gazdecki’s current business, he bootstrapped the company for a year before his personal goals with the business changed. MicroAcquire provides a marketplace for startups—many of which are bootstrapped—to get acquired, and he saw the market opportunity for the company grow with increased M&A activity last year.

MicroAcquire has now raised more than $11 million in venture funding from investors including Bessemer Venture Partners and Shrug Capital.

“I got to the point where I said, ‘let’s put some gasoline on this,’” Gazdecki said. “My personal ambition changed: Instead of this being a two-, three-person business where I have to slug it out for years, I wanted to accelerate that business.”

“I think a lot of these companies that bootstrap for a while, they get to a point where they’re already financially secure,” Gazdecki said. “They built a business where they own the majority of it, they can have a liquidation event … so I think founders get to the point where they look at the market and go, ‘Wow this market is way bigger than when I first started and my ambitions have changed.’”

Some founders are resistant to the idea of taking on venture capital and diluting their ownership and control in their companies. Wong noted that it took somewhere around 2.5 to 3 years to convince Atlassian to take funding from Accel.

“Part of it is a matter of trust. ‘Will the new money people, the finance people, come in and change our culture? Will they encourage us to do things that we might regret?’” Wong said.

Accel encourages founders of bootstrapped companies the firm is pursuing to talk to other bootstrapped founders who have received investment from his firm, Wong said.

Sometimes bootstrapped founders who have taken VC dollars from Accel refer another bootstrapped founder. Ohio-based homebuying company Lower, for example, was connected with Accel through the founder of Galileo, another Utah-based bootstrapped company that Accel invested in.

“It really rests on the foundation of, ‘do they trust the other person on the side of the table and is there evidence that they’ve acted with integrity in many other situations?’” Wong said.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

67.1K Followers