By Russ Wilcox

Founders spin a vision to attract investment dollars, then race to turn that vision into reality.

But what if the tide goes out faster than you expected? That’s happening right now for a lot of startups because of the capital markets. Inflation is up, valuations are down and the VCs are about to see you’re behind.

You may need to drop your share price to raise more money. That’s called a “down round.”

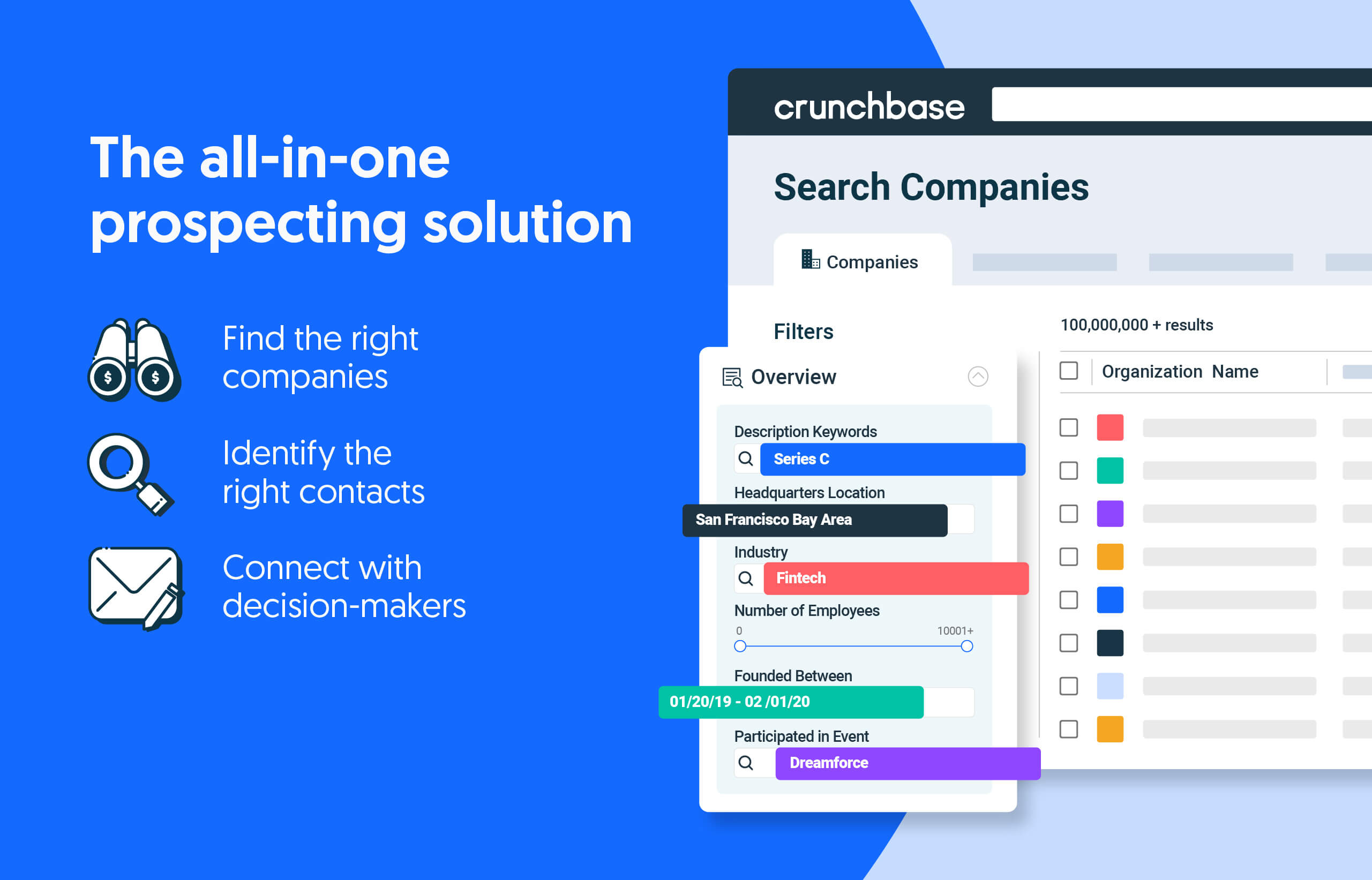

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

We had three painful down rounds at E Ink while I was CEO. Eventually we sold the business for a half-billion dollars and everyone celebrated. But we only survived because of those down rounds.

Here is what I learned:

Crash course on cramdowns

When a company is troubled and markets are tight, supportive investors usually just pass the hat around. Everyone shares the dilution.

But what if a major investor refuses? That firm becomes “deadwood” because the upside value of their shares relies on the other investors to keep taking more risk.

Knives come out. The down round becomes a “cramdown.”

A cramdown resets the stock price close to zero, which dilutes any nonparticipating investors down to zero ownership. But, that also washes out the founders and the option pool.

Investors prefer that management owns 15% to 20% so they usually “recharge” the team with fresh stock that must be vested over four more years.

Dismal days of delicate dancing

The months before our down rounds were awful. Our business struggled. Everyone felt dejected. My family was living on one income with kids and I needed to keep my job. That wasn’t easy because the board fractured into three camps:

- Those with deep pockets who smelled opportunity and wanted a quick cramdown.

- Those with small pockets who wanted me to find any zany new investor who would pay a high price. They were neutral on a cramdown.

- The third group was out of cash. They wanted me to fire-sale the company, or cut headcount to the bone. Even mentioning a cramdown made them furious.

There was no way to make everyone happy.

If you cram, cram all the way

My first down round went poorly because I listened too closely to that last group. Many were early backers or past co-founders and I felt terrible they would lose everything.

I fought against a total cramdown and managed to save 10% ownership for them, not realizing how much that angered the investors who were writing checks. Unwise.

Later, we went for a new raise and I learned another tough lesson. Most outside investors passed, “Too much deadwood on the cap table.”

Oops. We needed a second cramdown. Our team was again washed out and reset. Painful.

Friends, if you need a cramdown, embrace the low price and fully eliminate your deadwood.

Hindsight and humility

Raising money at a sky-high valuation feels like a big win on the day you close. But it also raises expectations that much higher.

The consequences of failure are asymmetric. If you stumble and need a down round, the VCs just write a check or even buy more on sale. Whereas you can lose all your shares, all your vesting, or even your job. Those are years you cannot replace.

So be prudent. Leave enough room to be sure of raising the share price in the future, even if you make mistakes and even if the markets are down.

In short, enjoy your swim. Just please keep your suit on.

Russ Wilcox is a partner at Pillar VC, a seed-stage firm based in Boston. He has 20 years of startup operating experience and has co-founded three companies. Wilcox was a founder and CEO of E Ink, which commercialized electronic paper displays invented at MIT. The company reached $200 million in revenue and was acquired for a half-billion dollars in 2009.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of a suitcase stuffed with money. Megafunds [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Megafunds-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of a man sitting on a huge pile o' money. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Giant_Funding-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of agentive AI brain - Europe - Quarterly. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Agentive_AI_europe-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers