As the IPO pipeline remains frozen solid, more noise is being made concerning employees options expiring or being extended.

On the day it was reported that payment titan Stripe put a tentative timeline on a long-awaited IPO, news also broke that the company would look to raise billions from private investors. The funds will be used, in part, to help offset a tax bill that will come due when it modifies employees’ stock grants that are set to expire.

Geolocation startup Foursquare won’t have to face a similar tax bill, as it was reported the company is letting some employees’ options expire.

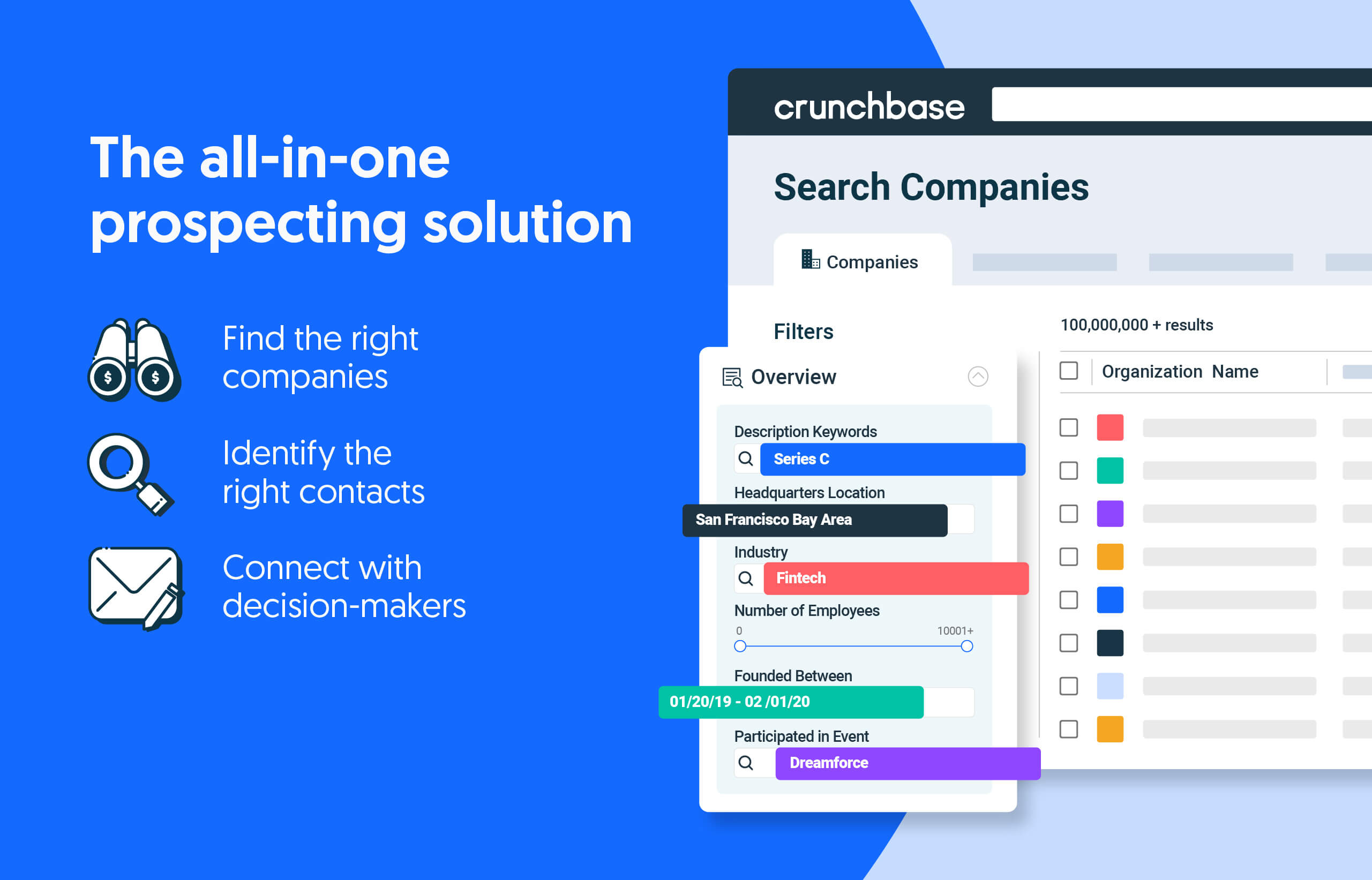

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Startup employees’ options typically expire in 10 years. Not long ago, that seemed far from a problem as companies typically would have some type of exit to give employees the liquidity they earned well before that time period ends.

Now, with companies staying private longer, startups need to keep an eye on not just their runway, but also the option clock.

Staying private longer

While some point to changes to the regulation regarding the number of investors a startup can have as playing a significant role in companies remaining private longer, those in the industry say basic economics is at work.

Before the JOBS Act was passed in 2012, private companies could only have 500 investors on their cap table. After the act was passed, that number jumped to 2,000 and excluded employees who held options.

Before passage, companies like Google (which went public in 2004), Facebook (which went public in 2012) and others were basically forced to go public as they were falling out of compliance with the rule. Startup employees would sell shares to interested investors on the secondary market and the company’s ownership numbers would explode.

However, Andrew Thorpe, a partner at Gunderson Dettmer’s San Francisco office, said the rule change likely is not why startups are staying private longer — but rather it’s the incredible amount of money available on the private market.

“Basically, large unicorns just raise capital the old-fashioned way,” said Thorpe, who advises management teams on securities regulation and public offerings among other things. “They are really in demand and companies with the most demand do not have a problem finding investors. And there’s just more money in the private markets.”

Restricting transfers

However, around the same time as Facebook’s IPO and the investors rule change, some companies started to introduce transfer restrictions into their option plans, which limits an employee’s ability to sell their shares unless approved by the company.

“We never really saw transfer restrictions, but around the time Facebook went public we started to see it more,” said Elizabeth Webb, a partner at Gunderson Dettmer’s Silicon Valley office and co-head of the executive compensation practice.

Such restrictions are now the most common among later-stage private companies, said Yokum Taku, a corporate and securities partner at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati and a co-leader of the firm’s emerging companies practice.

While the restrictions help keep a company’s cap table cleaner and more in control of who owns shares, it also can keep the clock ticking on employees’ options as companies remain private.

Webb said she is seeing the issue creep up more on private companies as they navigate the private sector longer.

“It’s a problem that has plagued the industry for a while,” she said. “With companies staying private longer, we will see more of it. We’ve seen more of it in the last several years.”

Changing rules?

With the massive amount of money available on the private markets, it’s also an issue not likely to go away soon.

However, one way to solve the issue would be if companies resumed going public earlier. Thorpe, who served for six years at the Securities and Exchange Commission, said since the JOBS Act the SEC has tried to streamline the process to go public to make it more attractive to companies.

There also are a couple of proposed changes the SEC may look at that might affect the pace at which VC-backed companies look to the public markets.

One proposed change would amend the “held of record” definition, which could alter how investors are counted. Instead of a special purpose vehicle being counted as one investor, the proposed change would instead count each individual investor in the SPV — significantly pumping up the number of investors in any company.

The other change — which has received more attention — would require more financial disclosure from private companies raising cash. It’s possible such a change would make going public more palatable to companies if they have to disclose guarded financial info regardless of whether they were going public or staying private.

Both issues are on the SEC’s Regulatory Flexibility Agenda for further investigation.

“Some stay on the agenda for a long time, so we’ll see where it goes,” Thorpe said.

If private companies start looking to the public market earlier, perhaps employees can stop watching the clock.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Money - Illustration of a giant piggybank with a woman looking at it. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Big_Piggy_Bank-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers