It took a $22.7 billion loss to do it, but finally SoftBank has offered something conspicuously absent from the current boom-to-bust cycle of unicorn investment: An actual mea culpa from an investor acknowledging that maybe they let FOMO and valuations get ahead of themselves.

On Monday, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son uttered such an admission following the release of the company’s latest quarterly results, which were the worst in its history.

“When we were turning out big profits, I became somewhat delirious, and looking back at myself now, I am quite embarrassed and remorseful,” Son said at a news conference. The longtime startup high-roller pledged to pare operational costs and increase discipline for new investments.

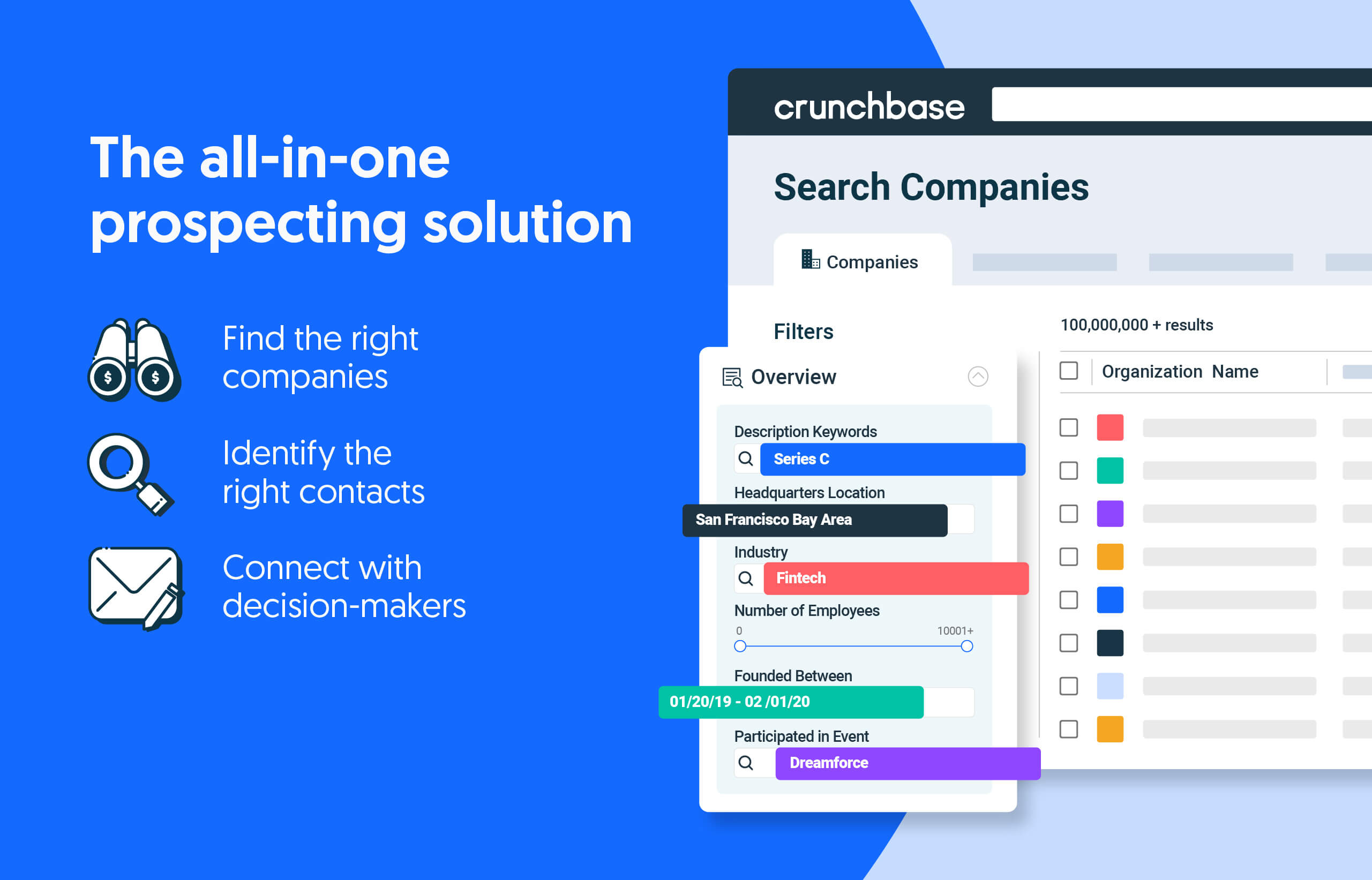

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Certainly the numbers were bad enough to warrant some reflection. SoftBank Vision Fund 1 posted a realized net loss of $22.7 billion, as many of its most iconic holdings, including Uber, WeWork and DoorDash, suffered sharp quarter-over-quarter declines on public markets.

For its newer Vision Fund 2, SoftBank observed that “the fair value of many privately invested companies has decreased due to the decline in stock valuations.” A case in point is Klarna, the buy now, pay later platform that recently closed on new funding after cutting its valuation a whopping 85% from last year.

Why admitting error is rare

Now, of course, losses in the startup investing game are far from rare. A clear majority of funded companies go on to fail. Newbie and veteran venture investors alike have bad years and bad fund returns.

But by and large, they try not to talk about it. One reason admittance of error is so rare in the venture capital industry is because of an unspoken rule of the business: One does not speak ill of portfolio companies.

Criticism of portfolio companies is more frowned upon the larger a stake one holds. Investors advise management, tout the company’s successes, and, when feasible, take board seats. Their role is that of boosters, not critics. And because of the long-term nature of startup investments, investors are typically locked into that role for many years.

In public markets, however, the same bonds of loyalty don’t apply. An investor who sours on management can offload shares with a few clicks. There’s even an entire investment category—short selling—for those who want to do nothing but criticize company performance.

So, once portfolio companies and their closest comps have hit public markets, it’s no longer possible to protect their image as high-flying unicorns. Numbers speak for themselves.

Take WeWork, which is arguably Vision Fund’s most famous investment. In its time as a private company, the co-working facility provider raised $10 billion in venture-backed equity funding and nearly $10 billion in debt financing. It was recently valued at $3.8 billion—which is very clearly more than $6 billion less than the cash investors put into it.

At this point, there’s rather little that can be said other than that, well, anyone who backed the company at its peak $47 billion valuation does, in retrospect, look kinda delirious.

Illustration: Li-Anne Dias

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of pandemic pet pampering. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Pets-2-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers