With more companies raising series Es, Fs and even Gs that eclipse half a billion dollars, now may be a good time to look at pro rata rights and how the investing world has changed for early investors.

While pro rata rights in the venture capital world are nothing new, as 2021 has seemingly rewritten the book on venture investment in terms of structure and money invested, it is interesting to think about the future of such rights.

A quick primer

Simply put, pro rata is a right that is given to an investor which allows them to keep their initial level of ownership percentage during later funding rounds. The investor is not obligated to exercise this right, but it is technically legally binding.

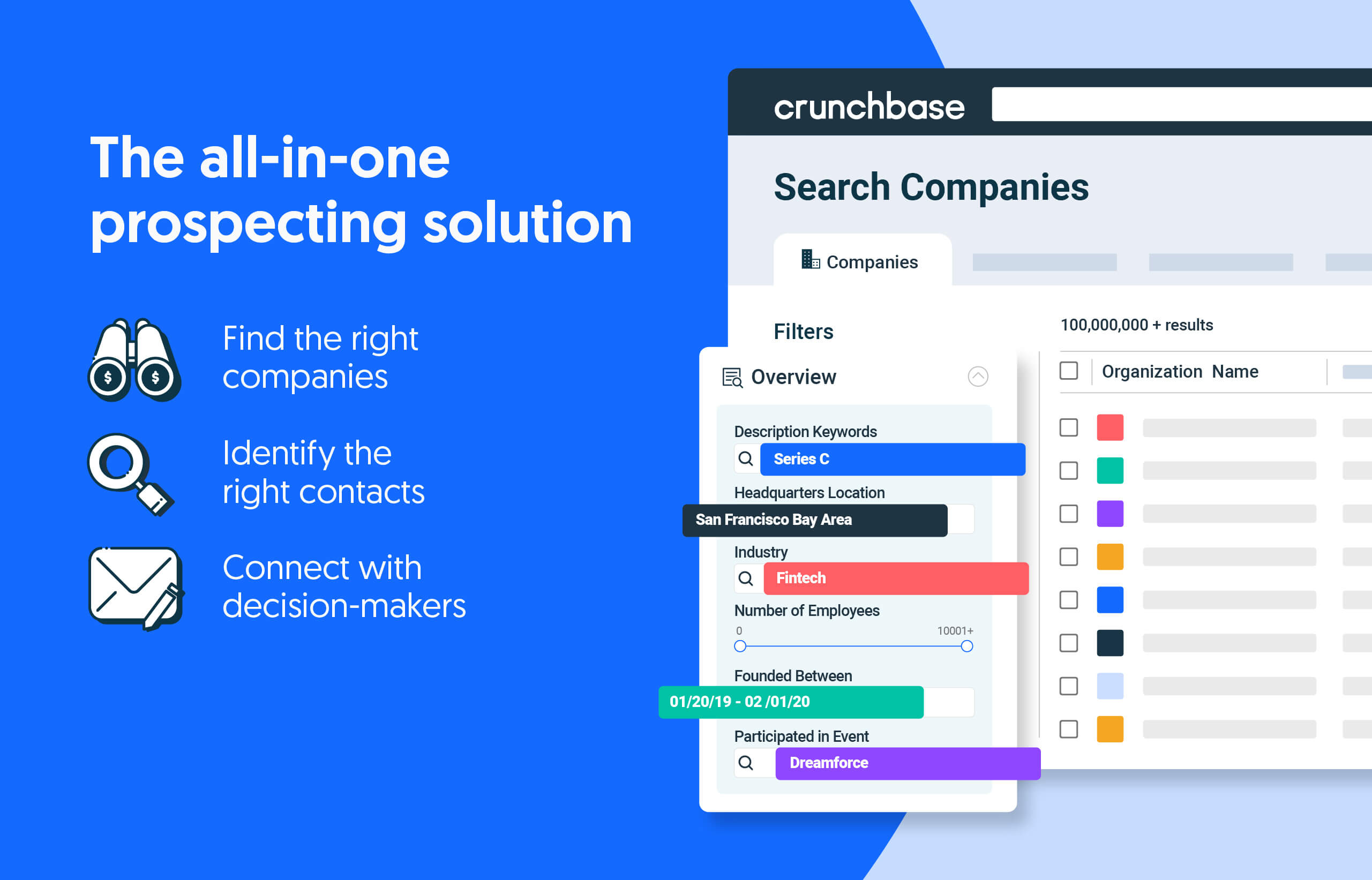

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

The easiest way to think of this is maybe to imagine an investor gets a 10 percent stake in a company after a seed round. The company raises a Series A by issuing more stock, which dilutes that investor. That investor, however, has a right to participate in that Series A to keep his or her stake at its previous level—hence the term pro rata, which is Latin for “according to the rate.”

There are potential benefits to both parties in the agreement. Companies offer them to give further enticement and security to a potential early investor in a fledgling new venture. The investor, meanwhile, gets to know that if a company does well, they have a guaranteed right to maintain their stake.

Not an obligation

While an investor can exercise their pro rata rights in the follow-up round, they are not obligated to do so. Sometimes investors choose not to because a company’s vitals may not be good and they do not want to place any further bets on it. However, quite often it comes down to simple economics.

“The firms just don’t have the money,” said Steve Brotman, founder and managing partner at New York-based Alpha Partners, an investment firm that specializes in partnering with venture firms to exercise the pro rata rights they maintain in companies. That model has allowed Alpha to invest in companies like Udemy, Cousera and Lime.

Brotman said he estimates small, early investing venture firms allow about 95 percent of pro rata rights to expire due to a lack of capital, funds needing to be closed, and the simple fact many of the firms are not growth round experts.

It often makes sense for investors. A small seed investor who may have invested $1 million for a 5 percent stake in a startup from a $20 million fund likely cannot now budget $5 million in a follow-up round to maintain that stake.

Larger rounds make it harder

That issue has become somewhat magnified as rounds have become larger and valuations have skyrocketed.

Once upon a time in the venture world, companies went public much younger, at much lower valuations, which could allow early investors to stay in the investment cycle. For example, in 1997, Amazon went public just three years after being founded and one venture round. The company raised $54 million in the IPO and had an initial market cap of $438 million.

On the flip side, Snowflake raised $1.4 billion in funding through eight rounds. The company went public eight years after being founded and raised nearly $3.4 billion in its IPO last year.

“There’s no doubt that has to affect investors exercising pro rata rights,” said Don Butler, managing director at Thomvest Ventures.

Thomvest made about half of its investments this year in seed rounds, and Butler said the firm continues to exercise pro rata rights at about the same pace it usually has through the years—although that has undoubtedly meant more money in recent years.

“Larger rounds and larger funds,” he said with a laugh.

Butler adds, however, what he has witnessed in the past few years are the top seed investors raising so-called “continuity funds”—used to exercise those rights and double down on portfolio companies that could be “winners.”

Before those funds came into being, Butler said, early investors would sometimes just raise special-purpose vehicles from their limited partners and others they knew to reinvest in current portfolio companies. Other times they would partner with other venture firms to help exercise those rights.

There are yet other times where investors just choose to stick with what they know.

“There are also just some investors that don’t want to participate in later rounds at all,” he said. “Their model is to invest early and they do it well, so they just want to continue doing that.”

Legally binding, but…

On some occasions, a company may go back and ask early investors not to exercise their rights because rounds are already oversubscribed and it wants to avoid further dilution. Such examples occasionally occur.

Brotman said while investors have the legal standing to exercise those rights, few ever push back hard for a simple reason.

“No VC is going to sue their own portfolio company,” he said.

It’s nice to know that even as much as the venture capital world changes, the constant of preferring to stay out of legal action with your portfolio company remains.

Illustration: Li-Anne Dias

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

67.1K Followers