The past week and half has seen a raft of back-and-forth news regarding Elon Musk and Twitter: Elon became the largest outside shareholder (but it’s a passive investment! Elon’s joining the board! Actually, Elon’s not joining the board!)

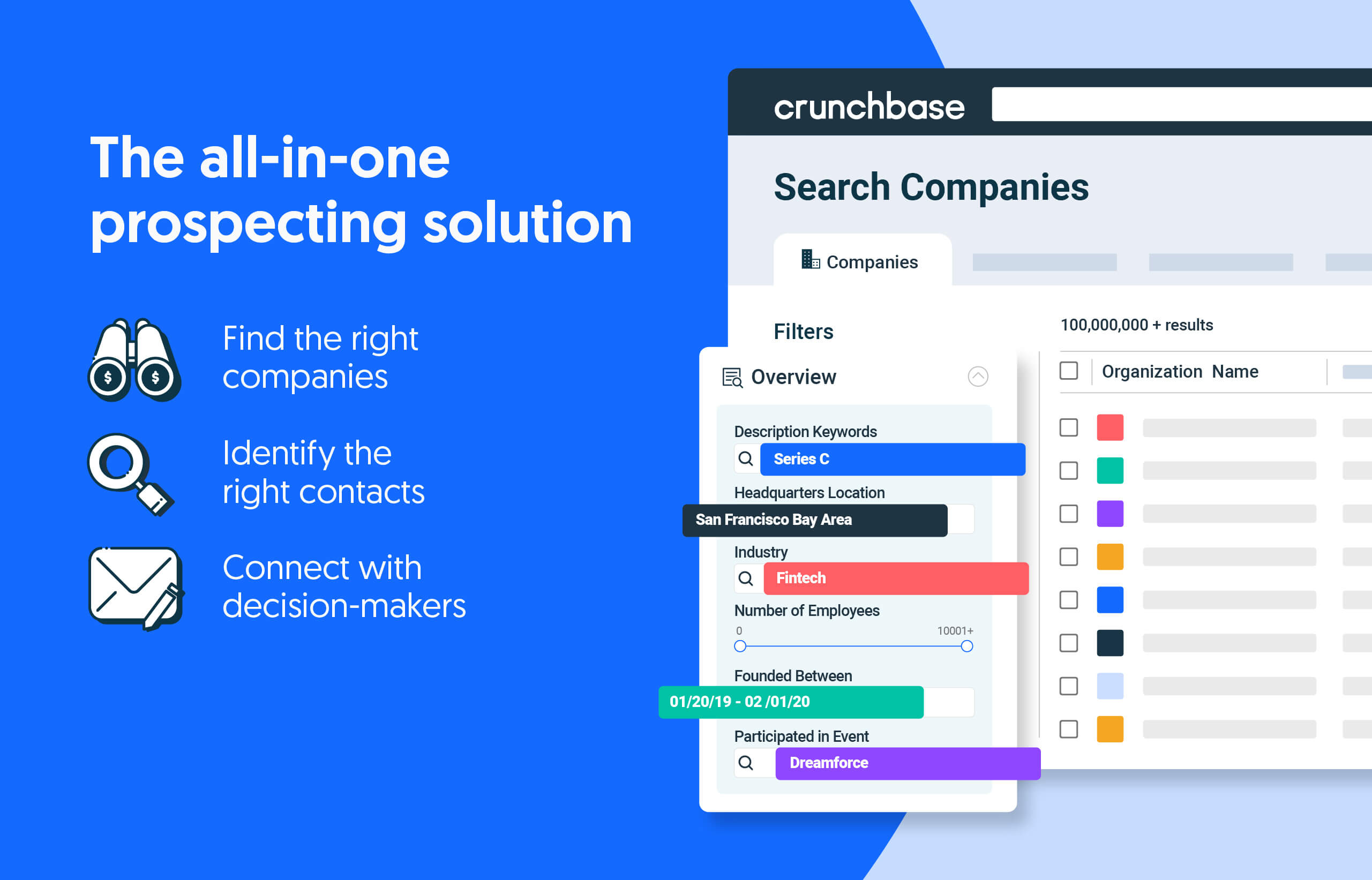

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

The latest development, of course, is that the Tesla CEO isn’t joining the Twitter board after all. The social media giant’s CEO, Parag Agrawal, said Sunday night that Musk declined the board appointment Saturday, the same day it was set to begin. And on Monday, Musk amended his filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission to become an active investor in the company.

The whole saga got me thinking about public company board appointments and Musk’s possible motivations to join Twitter leadership. So, I chatted with Aron Solomon, a lawyer who’s taught entrepreneurship at schools including McGill University and University of Pennsylvania, to learn more about how atypical the Twitter situation with Musk is.

How board appointments work

Public company boards work a little differently from those of private companies, since they have to adhere to SEC and other guidelines. Public companies headquartered in California, for example, must have at least one woman on the board of directors.

“Generally, somebody gets on a public company board because they seem to have expertise, governance skills that they can bring, some kind of representation to the board that hasn’t been there,” said Solomon.

The majority of the directors on the board need to be independent, meaning they don’t have a sizable stake in the company, didn’t work there in the past five years, and don’t have family ties to the company, according to Stefano Bonini, an associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, whose research has focused on corporate finance and venture capital.

Independent directors are compensated for their position, and generally come from the same industry as the company in question or have relevant business or regulatory experience.

While board members are typically selected during a shareholder meeting and are nominated by a nominating committee within the company, there’s nothing to prevent a shareholder from making a nomination.

“In this case, the fact that Elon bought a stake in Twitter didn’t involve, per se, any direct implication on his appointment as a director,” Bonini said. “You can have 50 percent of a company and have zero representation on the board. It’s possible. Now, is it common? No.”

Large shareholders are often appointed to boards, as we frequently see with private companies. Funding round announcements, for example, often contain the news of a new major investor joining the company’s board of directors.

Musk’s appointment to Twitter’s board of directors came with the caveat that he couldn’t own more than 14.9 percent of the company or take it over.

It’s also not uncommon for large shareholders to join a company’s board of directors, though the threshold is often higher than a 9.2 percent stake, as University of California Berkeley Haas School of Business lecturer Deepak Gupta pointed out to me previously.

Now that Musk won’t be serving on the board, that share cap doesn’t apply to him, Solomon noted. In theory, he could own a controlling interest in the company and push for change. Notably, Musk filed the necessary paperwork amending his status to active investor.

Going ‘overboard’

A recurring issue in corporate America—and something Solomon suspects was on the minds of everyone involved in the Musk-Twitter saga—is the idea of overboarding, or people serving on too many boards simultaneously.

“If you look at somebody like Elon Musk, I think it’s very, very clear that he’s already overboarded,” Solomon said. “Number one, he’s running his own companies.”

Musk is the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, and the founder of The Boring Co. and Neuralink. He’s a busy guy, no doubt.

In the case of Twitter, overboarding seems to be an issue the company is particularly sensitive about, given its past history of former CEO Jack Dorsey also being the CEO of Block, another public company.

“The biggest criticism you saw of Jack Dorsey in running Twitter was that he was divided in running Square and running Twitter,” Solomon said.

Activist investor Elliott Management Corp., for example, pushed for Dorsey’s ouster back in 2020, pointing to the founder’s divided attention between two public companies as a reason for some of Twitter’s woes.

Executives of public companies frequently serve on other boards—in fact, some are required to serve on nonprofit boards as part of their contract; that’s why you’ll sometimes see CEOs on the board of trustees of their children’s private schools; not only do their kids go to school there, but they have a contractual obligation to serve on a board.

To Solomon, it seems like Musk’s endgame was likely to take a controlling interest in Twitter—something he couldn’t do while serving as a board member.

“He’s probably thinking, ‘If I can have a controlling interest in the No. 1 social media outlet, it could benefit me in a lot of ways,’ ” Solomon said.

Bonini echoed that thought. “I think he has a view that rather than build a new platform from scratch, he might add value by bringing new ideas to the company, kind of like becoming a factor of change. That’s all I can think of in the ultimate intentions of buying such a stake.”

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration showing AI agents, depicted by robots, performing digital tasks. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Quarterly-agenticAI-global-470x352.jpg)

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers