It has been a banner year for teletherapy funding.

Per Crunchbase data, funding surpassed $1.4 billion worldwide so far in 2022, a huge spike from past years. Funding in the space leaped from the hundreds of thousands in the early 2010s to $418 million in 2018. In 2020, that number jumped to $1.23 billion. The number of venture-backed teletherapy startups has jumped as well, from 15 in 2010 to more than 100 today.

And this growth has been transformative: The current crop of teletherapy startups enjoying the flood of fresh funding bear little resemblance to startups of the past.

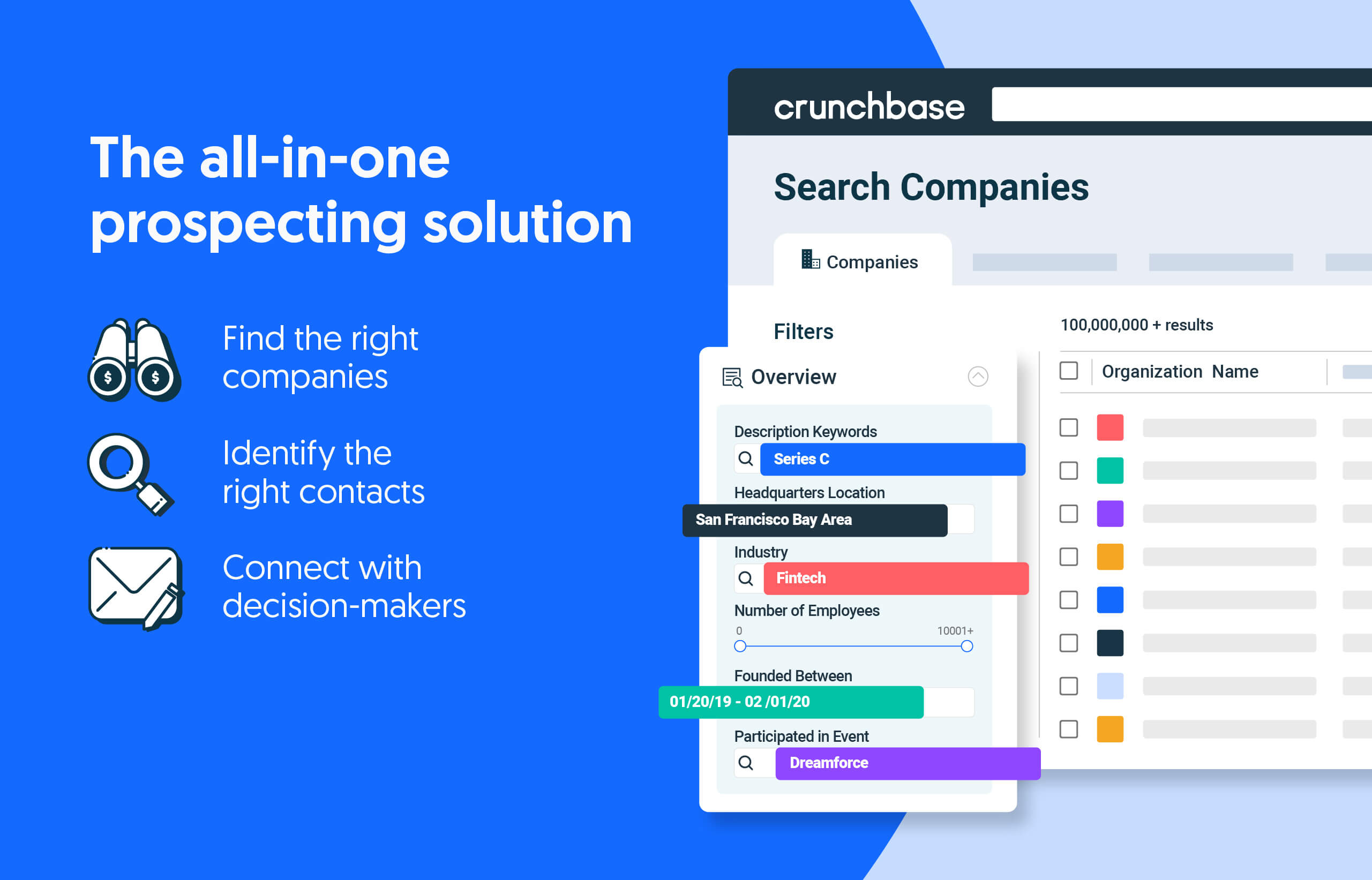

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

The first generation of tech-enabled telehealth platforms formed in the early 2010s at the nexus of three dramatic innovations. The 2010 Affordable Care Act largely required insurance companies to cover mental health resources. At the same time, the smartphone was becoming faster, more sophisticated and cheaper, driving companies to develop a wide variety of phone apps. And the gig-worker model popularized by Uber was seeing widespread adoption in workforces across all industries.

This pressure cooker of innovation and policy change has created teletherapy companies such as BetterHelp and Talkspace, two of the largest in the U.S focused on online mental health care. BetterHelp was acquired by Teladoc Health in 2015 for $4.5 million per Crunchbase data, and Talkspace went public in 2021 (and is trading considerably lower than when it debuted).

Currently, the second generation of teletherapy startups are operating much differently from the giants that preceded them, with the support of today’s venture firms.

Changing the business model

Telehealth companies of yore adopted a pay-out-of-pocket monthly subscription model that was, for a time, far more appealing than getting on a waitlist for the handful of providers in your network. Instead of billing insurance (a time-gobbling hassle), patients could pay a monthly fee to access their therapist for sessions. But the subscription model had its drawbacks.

“I think that was sort of a very heavy-handed approach from venture capitalists to put a business model that has worked in other industries on to mental health care,” said Claude de Jocas, vice president at Volition Capital. “I don’t necessarily think it was consistent with how patients or providers think about what really high-quality mental health care looks like.”

So Volition and other venture firms are funding teletherapy startups with a more traditional, insurance-based model. Path, for example, raised $80 million in February to connect people exclusively with in-network therapists. And Quartet Health raised $51 million in February to help insurance-based mental health providers find and manage patients.

“I’m just generally not super bullish on pure-play direct-to-consumer user acquisition in health care, and I want to see that the team is thoughtful about getting involved with payers,” said Kevin Zhang, health care-focused partner at Upfront Ventures.

Still, working with insurance providers is often difficult for therapists and often doesn’t pay as well as working as a private practice, which is why many therapists don’t take insurance. So a lot of these startups, like teletherapy-centric Alma, help therapists deal with administrative and billing chores which frees up time for the therapists.

“What’s interesting is these businesses have scaled quite high with consumers paying out of pocket,” said Larry Cheng, managing partner at Volition Capital. “So you can only imagine what the demand would be if there was insurance coverage.”

Changing the workforce

Another issue with the older generation of teletherapy products was the therapy workforce itself. Popularized by Uber, gig work became the darling of the tech world around the same time Talkspace and BetterHelp got started (in 2012 and 2013, respectively).

The use of therapy contractors, however, creates churn in the provider base — a suboptimal model for a treatment that requires strong rapport between patient and provider.

“The model isn’t designed for optimal care to patients, it’s designed to scale,” Cheng said.

As gig work has gone out of vogue, venture firms are turning back to full-time workers in the teletherapy space. Santa Monica, California-based Polygon, for instance, provides telehealth services for people with learning disabilities through full-time mental health professionals. California-based Sensible Care, which raised $13 million in June, fully employs its mental health providers.

Employing full-time therapy workers prevents churn and provides a more consistent experience for patients and a more stable revenue outlook for startups.

“Taking care of the provider as well, making sure that they’re happy, fulfilled, valued [and] treated well as employees is really a core part of the business,” said de Jocas.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of 50+ woman on smartphone. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Femtech_-300x168.jpg)

![Illustration of pandemic pet pampering. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Pets-2-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers