Here’s what happens in a health care utopia: You, the patient, have one health record documenting every allergy, vaccine and family history of disease since you were born. Instead of filling out new patient intake forms whenever you see a specialist or switch primary care physicians, your doctor can access your health record, add to it, and send it to the necessary health professionals in your life.

Building such a platform isn’t a particularly difficult technological task. And yet, most people can’t access their childhood vaccination records. Crunchbase data shows funding around health record startups is at $367 million, the highest it’s been since 2021, and 2022 isn’t over yet.

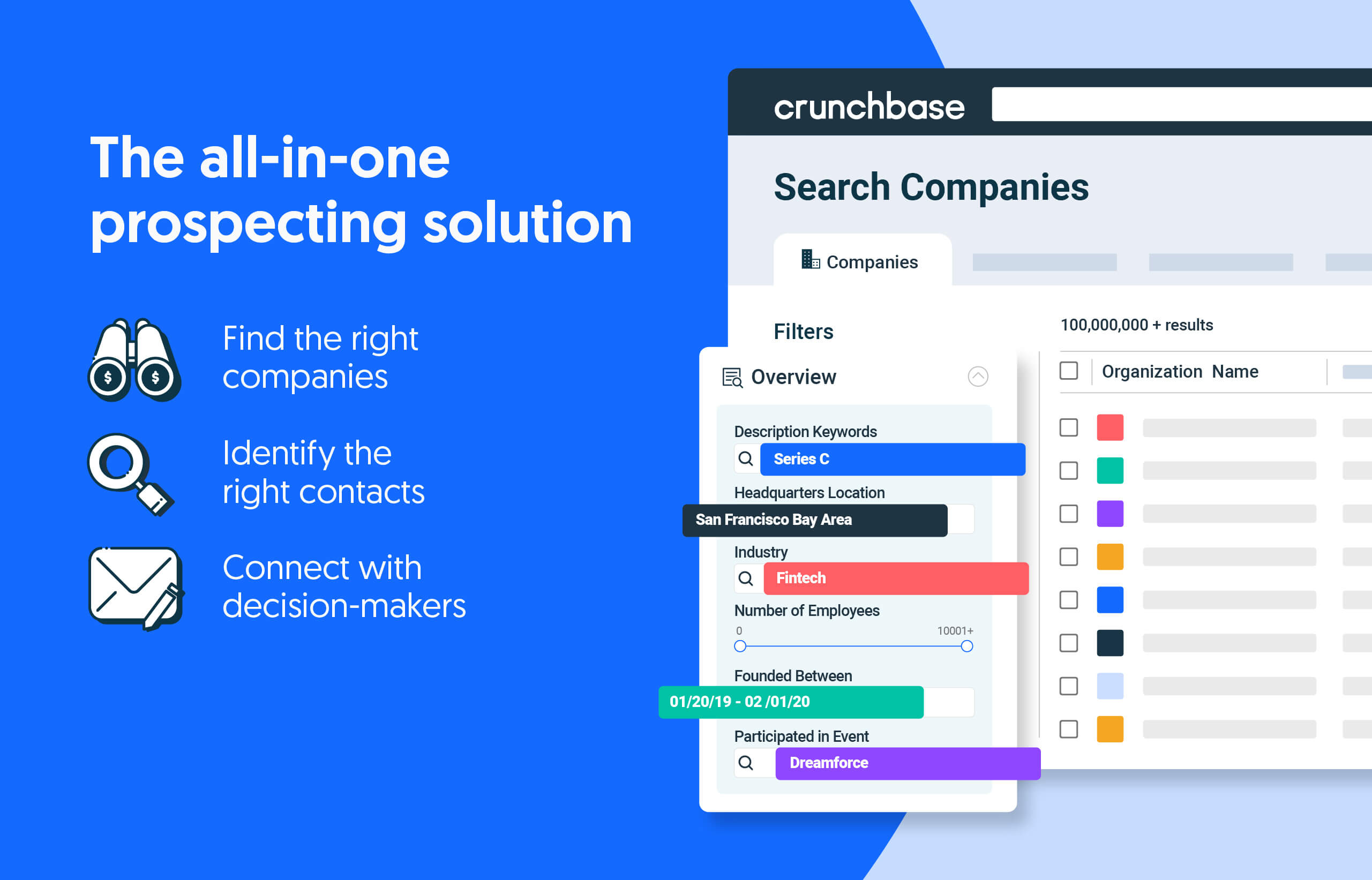

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

But despite rapid innovation in the space, electronic health records continue to be a thorn in the sides of physicians, raising doctor burnout rates, which slows their adoption and prevents us from reaching that health care utopia.

The problem, it seems, is not one startups can solve, at least not without mass cooperation between the many doctors, labs clinics and other health startups the technology tethers.

“When you hear clinicians constantly complaining about the increasing administrative burden and complexity; it became burdensome and complex because the technology allowed it to,” said Paul Chung, a Kaiser Permanente physician and UCLA health policy professor.

The story of the electronic health record is a perfect example of why technology adoption in health care lags behind every other industry. Such records are often trapped in a tangled web of siloed, disparate organizations that don’t work well together, leaving innovation behind.

Unraveling that tangled EHR web

The quality of care movement in U.S. medicine started in the 1960s to improve patient outcomes in the health system, and picked up in the ’80s and ’90s with the advent of data-storing computers.

Hospitals adopted complex enterprise-focused platforms to deal with a high influx of patients, and doctors’ offices began adopting similar technology in 2009 after the HITECH Act. HITECH was an Obama-era push to move patient data to the computer as part of a goal to connect the health institutions a patient has to navigate. But the shift to computers quickly proved challenging for health care workers.

“If you talk to most clinicians, I think that has sapped a lot of the joy of the practice of clinical practice from them,” Chung said. “But there’s also a general acknowledgment that there’s some need for oversight that you probably can only do with technology.”

The interoperability problem

Individual doctors and groups adopted expensive EHR systems that came with high learning curves. But none of them talked to each other. HITECH promised an easy and cost-saving future, but doctors still needed to fax patient information or enter it in multiple systems to update patient records.

“The first wave of healthtech said, ‘Well, if the doctor just entered more data into this record, we would get so much more,’” said Jacob Effron, principal investor at Redpoint Ventures who is focused on health care investments. “But doctors are so busy. It’s not realistic.”

Others blamed the EHR systems’ design. Epic Systems, one of the oldest and most well-known systems for hospitals, was pointedly accused in Congress of being purposefully closed-off. Receiving a digital medical record from companies like Epic came with steep fees. Epic fought back by pointing out medical institutions that used its technology had great interoperability. That didn’t help.

“It’s like the 800-pound-gorilla problem,” said Kevin Zhang, health care-focused partner at Upfront Ventures. “The incumbent EHR vendors are pretty nefarious with how they’ve locked up the market. It’s basically created IT systems that [makes] hospitals extremely challenging to integrate into.”

Plus, hospitals themselves have an incentive to maintain independent EHR systems. Epic customizes specific functionalities for different hospital systems to build exactly what they need. That means the platform in one health organization looks drastically different from another. If you were a hospital that paid Epic to do this, you might want to make it easier for patients to go back to you instead of taking your records and visiting another.

One step closer

The pandemic brought another wave of innovation to the space. As health centers began adopting telehealth and virtual visits, it suddenly became important to put everything that happens at a doctor’s office — scheduling appointments, filling out intake forms, billing — online. Doctors turned to their EHR.

Funding for EHR tech startups rose from $98 million in 2020 to a whopping $751 million the following year, a 666% increase, according to Crunchbase data. Meanwhile, a second wave of companies is looking to better integrate with existing electronic health records thanks to the adoption of FHIR standards in 2020. FHIR, or Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, is a set of standards meant to make it easier for companies to share data.

One of them, Redox, has raised $95 million since it started in 2014, according to Crunchbase. The platform connects providers with a slew of different billing platforms, remote patient monitoring systems and telehealth startups to custom-build an administrative solution for doctors. Another, Health Gorilla, raised $50 million in March to improve flow of patient information between providers and payers.

While several of these new companies are promising and intuitive, they’re not that useful to the largest hospital systems in the country without buy-in from the big EHR players.

“Even if you got the buy-in from the [hospital] CFO or business leadership, that integration work into the hospital is a nightmare and pretty bespoke every time. So that’s why it’s so tricky,” Zhang said. “And they have low margins to begin with so they can’t take on giant projects all the time.”

This is, ultimately, the crux of all health care investments: The markets in health revolve around patients, providers or insurance. Without buy-in from those markets, regardless of how good the technology is, startups are doomed.

“That’s the fun of health care investing,” Effron said. “What can make it so complex is it needs to work for a lot of different people in the system.”

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers