Thomas Carence from Kansas City, Missouri, set out to improve a cure for hay fever in 1901 by connecting two gauze-filled cylinders that fit inside the allergy sufferer’s nose, a solution he patented. Little did he know, he was more than 100 years ahead of his time.

Subscribe to the Crunchbase Daily

Although Carence’s solution appears to be among the earliest efforts to claim the idea of in-nose air filters, more followed. But those products, if they ever moved to an iteration beyond patent office filings, never really made it to the mainstream.

That may change as a small but growing cohort of startup founders aim to commercialize wearable and individualized products to battle against growing air pollution, allergens and, to some degree, even airborne diseases like COVID-19.

When those founders talk about the future, they see a not-too-distant reality where the average consumer might breathe in a solution that can help protect the lungs as part of their morning routine. In this version of the future, people not only pat their pockets for their keys and wallet, but also grab their in-nose air filters before walking out the door.

“I expect 10 years from now people will be hydrating their airways with the meticulousness and the care that they wash their hands or brush their teeth,” said David Edwards, a Harvard University professor and founder of FEND, which makes a device that mists moisture and minerals to help clean and hydrate air passages. “It’s all a matter of data; there’s no disease that is more deadly today and on the rise than respiratory disease.”

Boston-based FEND is distinct from many of the other personal air filtration products hitting the market because one doesn’t wear it; they breathe it. The water, salt and calcium in the solution aim to boost the air filtration system already in our bodies, promising to stop a portion of pollution, allergens and germs in the upper airways, keeping them from reaching the lungs or being spat back out into the world, Edwards said.

The product builds on Edwards’ work in the early 2000s, when the fear of anthrax arriving in American mailboxes was at an all-time high. The U.S. government, aware of his research on diabetes medication that could be inhaled, enlisted Edwards’ expertise to help mitigate the danger of a new threat.

Edwards found that a good portion of the bad things in the air—from pollution to allergens and even anthrax—could be caught before reaching the lungs if our air passages get a little extra TLC with moisture and minerals. But as the threat of anthrax faded into the background, so too, did his work on the project.

The COVID-19 pandemic seemed an obvious time to bring the research back, even if FEND’s long-term goal didn’t revolve around a single virus, he said. The company has raised $18 million in venture funding and is planning a Series A round next year, Edwards said.

Those that use the product say it helps with allergies, sleeping better and reducing asthma symptoms, though Edwards is working on more studies to collect data that may help validate those observations, he said.

“If you look at people who bought FEND to date, I think it’s fair to say they mostly bought FEND out of fear of COVID,” Edwards said. “But they mostly use FEND because it’s helping them breathe better.”

Breathing easy

As Carence’s patent filing shows, worries about the air we breathe aren’t new.

European doctors in the 17th century wore beaked masks to avoid the plague. Americans invented devices in the 1800s to help firefighters filter smoke out of the air and the first gas mask was patented in 1849. Later, air filters became standard in homes and offices to sift out dust and dander that collects indoors. Today, an endless variety of paper and cloth masks promise to help protect us from COVID-19.

While the founders behind the budding industry of individualized air filtration claim their products could help slow transmission of the coronavirus by blocking droplets from entering the nose, or, in the case of FEND, ensuring those virus particles stay caught in the throat rather than splattering back out into the world, none said they want to replace masks that cover the nose and mouth.

Even so, many potential consumers have had a hard time not viewing the products through that lens.

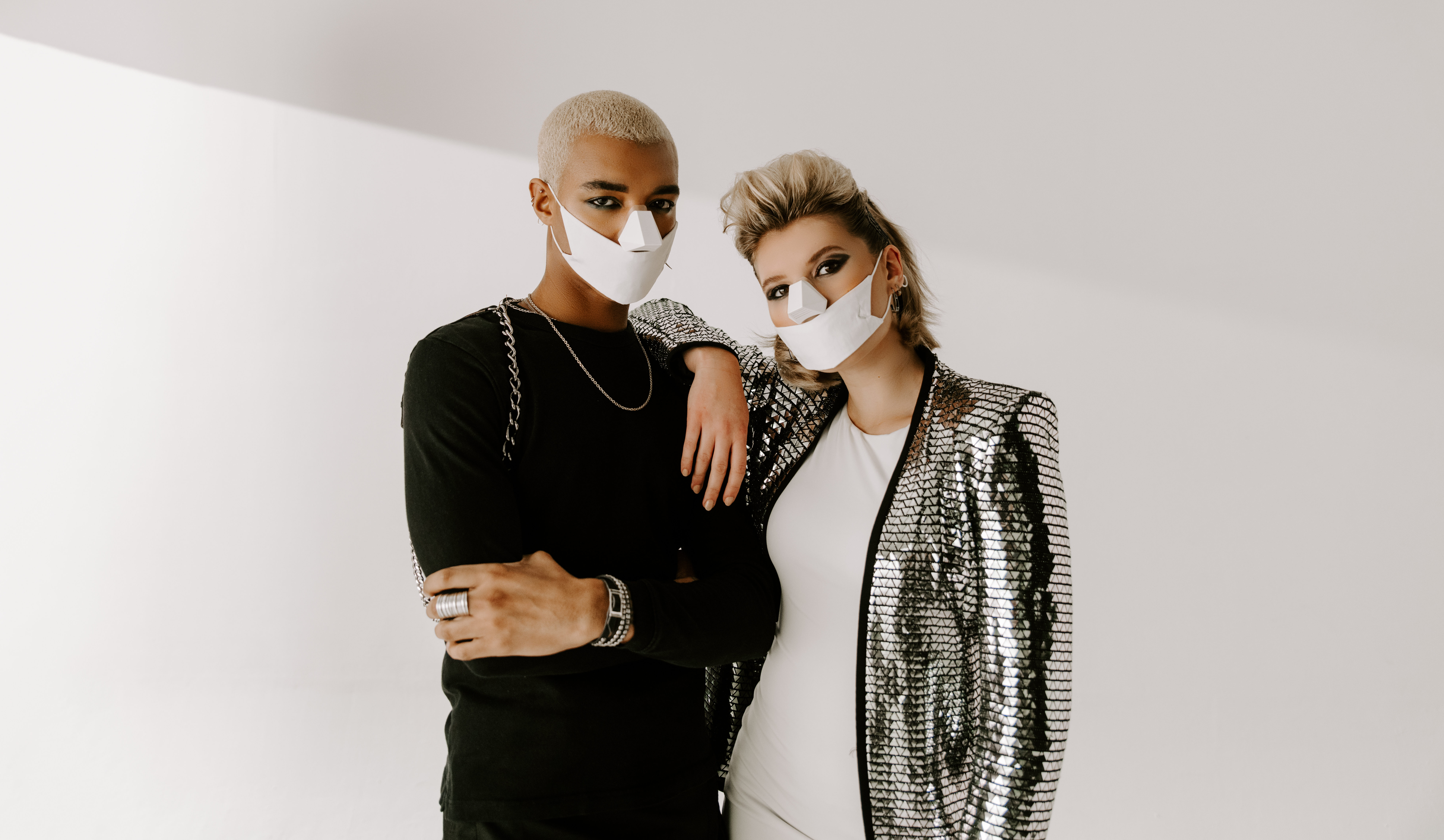

“It was a crazy time to be launching this right before COVID,” said Carina Cunha, founder of London-based Nosy, a triangular air filter that seals around the nose. “A lot of people were very confused in the process and thought that we were for COVID, and that we were really stupid for not covering the mouth, so it was a really, really difficult first year.”

In fact, Nosy was launched in January 2020 when Cunha, reeling from a cancer scare, wanted to take control of her overall health. Air seemed like an obvious place to start, she said.

“I don’t want to depend on politicians making laws that may make a difference 10 years from now, in order for me to be happy and healthy,” she said. “I want to be able to take the tube or the underground, and I want to be able to be on a busy road or near people that are smoking without it impacting my health. … For me, it was a lot about empowerment.”

At their core, in-nose air filters are aimed at shrinking the pollution and particulates that enter one’s lungs on a daily basis and that contribute to the 6.5 million annual deaths the World Health Organization links to poor air quality globally.

Nosy is set to launch its next iteration early next year, an in-nose filter that could one day come equipped with an air pollution sensor, Cunha said. She’s hoping the new filter will draw more venture capital—particularly from the American market—to scale production and, in turn, bring down costs for consumers. So far Nosy has raised 43,000 pounds, which translates to about $48,000 in venture funding, in a small Angel round, Crunchbase data shows.

Air control

The timing for such a product may, unfortunately, be good. The United States this year saw its hottest summer on record and climate and fire experts warn that the wildfires that devastated entire towns in California and flung tiny particles in the air may become an annual event.

Despite those issues, it’s worth noting that air quality in the U.S. has improved overall in the past two decades, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows. But a deeper look at the information shows those improvements are felt unequally across the country and sometimes even block to block. Last year, many U.S. cities saw more days of unhealthy air quality than in previous years.

Taken as a whole, the air people breathe on Earth is unhealthy, according to a 2020 report on the matter published in Nature journal.

The ideal solution is that pollution would decline so no one would feel they need to wear filters due to air quality concerns, said Sophie Frank, CEO of San Francisco-based in-nose air filter company Resprana. But that’s not the reality today for many people, she added.

“There is a hope that we can better address exposure to air pollution at the root of the problem and decrease pollution,” she said. “There’s also the unfortunate reality that there’s a lot that we already cannot affect that’s in the near-term.”

Resprana, which launched its in-nose air filters, called Duo, through an Indie-go-go campaign, is now sending pre-orders for its early backers and has gotten them into the hands of about 150 people.

Feedback from those customers is teaching the company where to go next, including offering a larger size and pointing out some use cases they hadn’t considered before, Frank said. She hopes to open sales to anyone in the first quarter of next year. In the meantime, Resprana has already secured a utility patent to explore aromatherapy or medication delivery mechanisms using its wearables in a future iteration.

Like Cunha, Frank views her nose air filters as a means to empowerment.

To her that looks like “unabashed boldness that comes with this kind of odd-looking metal component that sticks out of the nose that people may not have seen before and … wearing that as a sign of, ‘Hell yeah, I’m protecting myself against this crappy air that, unfortunately, we’re all breathing,’” she said.

“I think that the future we’re moving toward, and are already partially experiencing, is that our accessories serve us,” Frank added. “This idea of integrated, wearable health tech has certainly been on the rise.”

Market studies

But while much of the individual wearable and spray-able air filter industry seems to be getting their bearings, 02 Nose Filters is finding its stride.

Dan Voetmann launched his O2 Nose Filters about six years ago, first targeting industries where flying particles were of particular concern, like construction, dentistry and even policing, as officers don’t want to breath in lead during shooting practice.

Since then, sales have increased by 200 percent to 300 percent annually as Voetmann has whittled the price per nose filter down to about $1 apiece. Consumers can find the disposable filters on Amazon.

Voetmann launched 02 Nose Filters without venture backing. But like other founders in the industry, he thinks nose filters will become more widespread and common, so he’s considering seeking new capital to expand and iterate on the product as the market grows. Ironically, adding more companies to the space could help, he said.

“One thing that’s very true in retail, especially if you’re launching a new product category, is it has to gain some traction and I can’t do it all myself,” Voetmann said. “I would love to have some fantastic competitors out there doing this to build the category, and I just want our share of it.”

As a serial entrepreneur with a background in marketing, Voetmann is not in the filter-making business. That’s why he opted out of making his own proprietary filter and instead uses 3M’s filters through an agreement with the Minnesota-based company.

Using a product that is already tested and trusted, he said, will help set his nose filter apart. “I would say that’s the most important thing if you’re choosing a nose filter,” Voetmann said. “Find one that you know what level of protection you have.”

Time for takeoff?

Making the case for filtering the air we breathe isn’t hard. But it’s still unclear whether this is the moment that in-nose filters and individual filtration devices will actually take off.

Deena Shakir, partner at VC firm Lux Capital, said she’s skeptical that everything has aligned—from consumer demand to clinical validation—to make the future of air filtration live in our noses each day.

But, she said, if this were the moment the technology were to take off, there are several key factors that investors and customers will be looking at closely. Affordability will be one. Customers will want to know the products are comfortable and environmentally friendly, she added. But the most important question is: Do they work?

“I haven’t seen enough to think that this is where we’ve hit an inflection point on clinical validation, but we may have hit an inflection point for the consumer,” she said. “It does feel like we’re all, as humanity, thinking of how we’re going to move to a world where we can at least not be in masks all the time.”

Images courtesy of Nosy.

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of a guy watering plants with a blocked hose - Global [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/quarterly-global-3-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers