When the IPO window is wide open, companies try to jump through. It’s an opportunity that attracts startups across stages, even some that might, under less buoyant market conditions, have waited.

The bull run that peaked late last year was no exception. Far-from-profitability companies in sectors from fintech to electric vehicles to enterprise software carried out the biggest debuts in years. Meanwhile, scores of lesser-known startups tapped public markets in SPAC merger deals.

It all worked out very well. Until it didn’t.

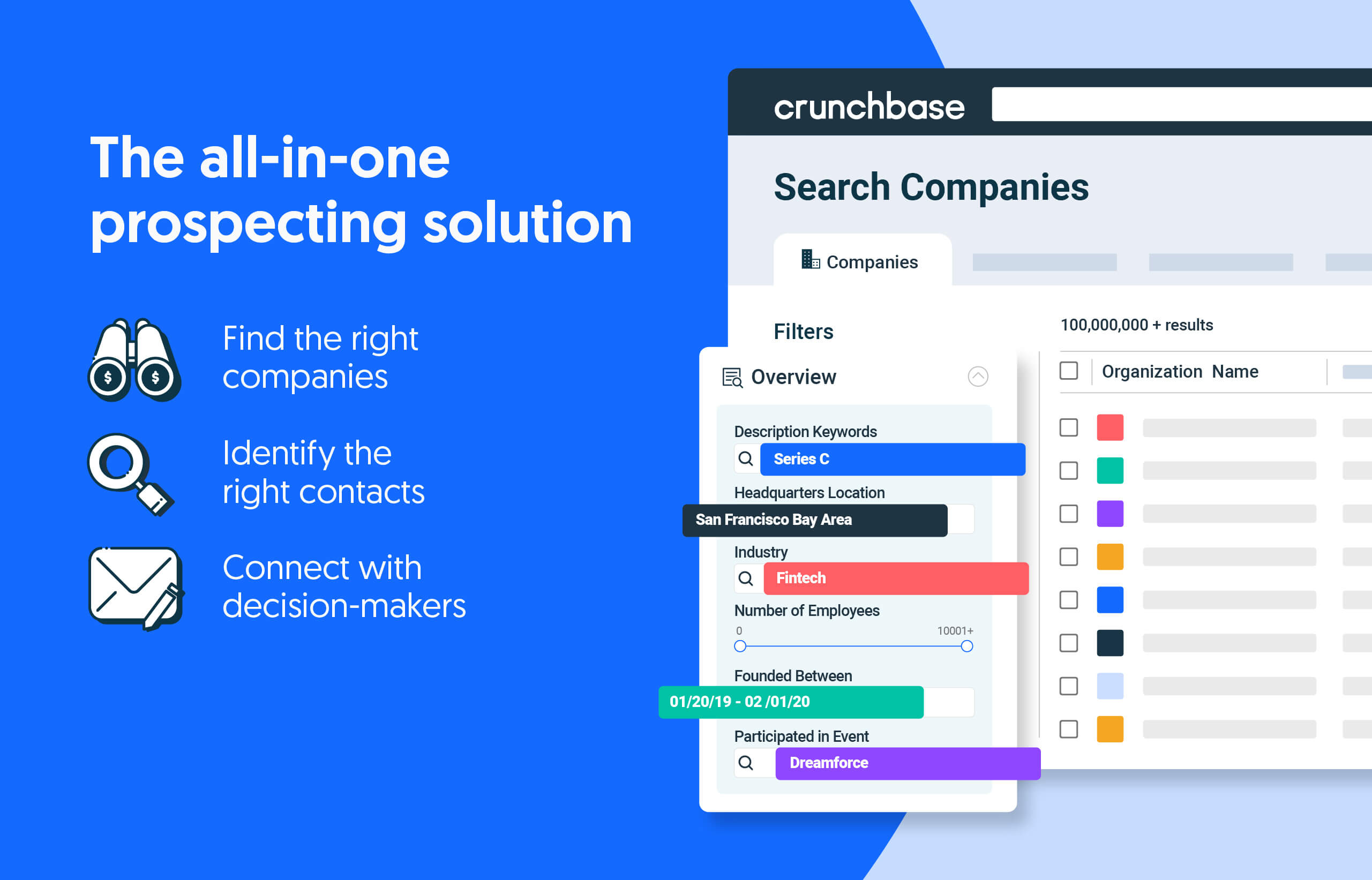

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Currently, virtually every venture-funded company that went public in 2020 or 2021 is trading at a fraction of its former high. The hardest hit have largely been those who took the SPAC route to market, many of whom are now seeing shares plummet perilously close to delisting territory.

Which brings us to the question at the heart of this column: Did too many companies go public too early in the past couple years? Should they have waited until they could deliver the kind of predictable earnings and growth trajectories that public investors favor?

Too early? Maybe not

Well, maybe. But maybe not.

This muddled take is what happens when you begin researching a column with one opinion, only to end up with a different one. The logic is that despite how terribly so many recently public companies have performed, it’s not always clear they would have done better staying private.

Of course, the perspective of a public company investor tallying large losses from early SPAC deals will differ. In their eyes, companies clearly went out too early.

Per Lise Buyer, partner and founder at Class V Group, a consulting firm for IPO candidates, there is very little doubt that many companies chose the SPAC route because they weren’t ready to face the scrutiny applied by investors in traditional offerings. To a large degree, those companies bought the rhetoric that it was a quicker, easier way to go public.

“In fact, for most it proved to be neither and the result is that a number of not-ready-for-prime-time companies jumped to the public markets before sturdy infrastructure was in place,” Buyer said.

But while the Class of 2021 IPOs are definitely not trading well, Buyer adds, those companies do have significant money in the bank to fund their operations. “Given that most tech stocks have taken a hit these last few months, many of the recent IPOs did exactly the right thing to raise money while ‘the gettin’ was good,’ ” she observes.

So, while investors might not be happy, companies themselves managed to raise significant funds to help get through a protracted down cycle.

Historical trends around IPO timing

Still, the disappointing performance of recently public companies gives reason to consider whether the next crop of new market entrants will be a more mature cohort.

Already for tech, companies pursuing traditional IPOs have been trending older. From 1980 to 2021, the median age of a technology company going public was eight years, per research from Jay Ritter, a University of Florida finance professor. In three of the past four calendar years, meanwhile, the median age was 12 years.

But those medians have shifted dramatically year to year. During the tech stock boom of 1999, the median age of a tech company at IPO reached a low of 4 years. Amid the market downturn of 2008, it reached a high of 14 years.

The largest traditional venture-backed IPOs of last year were on the mature side. They included electric vehicle manufacturer Rivian (founded in 2009), crypto platform Coinbase (founded in 2012), and enterprise software provider UiPath (founded in 2005).

Ritter’s data did not include tech companies that went public via SPAC, which tend to be younger. Per Crunchbase data, the median founding year for VC-backed companies that went public via SPAC in 2021, for instance, was 2013. By comparison, the median founding year for VC-backed companies that went public through a traditional IPO or direct listing was 2010.

Some of the VC-backed companies to go public through a SPAC last year were especially young. They include Archer Aviation (founded in 2020), Bakkt (founded in 2018), and Hyzon Motors (founded in 2019).

Since the above-mentioned companies have all performed poorly, it seems reasonable to presume investors would stay away from such young offerings in the future.

The case for (maybe) not waiting

That said, there’s a case to be made that the best returns come to those who made the right bets on very young companies.

After all, Apple went public when it was little over four years old, observes Chon Tang, founder of the UC Berkeley SkyDeck Fund. And while shares of most youngish companies that went public in the past couple years are way down, he’s still quite impressed by the underlying technologies they’re developing in 3D printing and other sectors.

Impressive technologies, however, typically aren’t enough, long term, to sustain investors’ interest, Tang observes. Public shareholders also want some predictability around earnings and revenue growth, which is something upstart companies aren’t usually well-positioned to deliver.

Probably some of today’s seemingly too-early-to-market companies will eventually mature into the predictable revenue-generating machines that investors’ favor.

“Just as in the 2000 and 2008 downturns, those that use their resources effectively will thrive during a recovery and the others will go away,” Buyer predicts.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of N. America-labeled piggy bank on an inclined plane. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Quarterly_n_am-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers