The scooter wars flared up seemingly overnight, driving huge amounts of scorn, hype, and fundraising as traffic-choked tech workers in California fell in love and hate with electric scooters brought to their cities by two now famous startups: Bird and Lime.

The scooter space quickly gave birth to unicorns, regulatory spats, lawsuits, and more. It was a wild ride for the companies and the tech industry as a whole.

But now some time has passed, and although scooters are very much still in the conversation, the early hype has faded. That brings us to a fun question: Are the scooter companies any good as businesses?

As capital-accepting and headline-generating vehicles, they are tremendous. But does that mean they’ll mint profits?

Index

The Bird Income Statement

Happily, after we spent time scratching about in the dark trying to answer our viability question without too much to work with, we have new data on Bird, one of the two leading American scooter companies, via this excellent report from The Information.

The report in question covers the company’s performance metrics: revenue (total money brought in from riders), gross margin (the percent of revenue that Bird has left over to pay for its operating costs, like office space and staff), and its costs of revenue (the money required to provide its basic service to customers).

The report’s data helps us understand Bird’s chance of long-term survival. It also helps us understand the scooter sector, as other key players have similar business models.

Constructing gently, here’s a partial income statement of sorts for Bird based on what The Information gleaned from a Bird investor digest.

Revenue

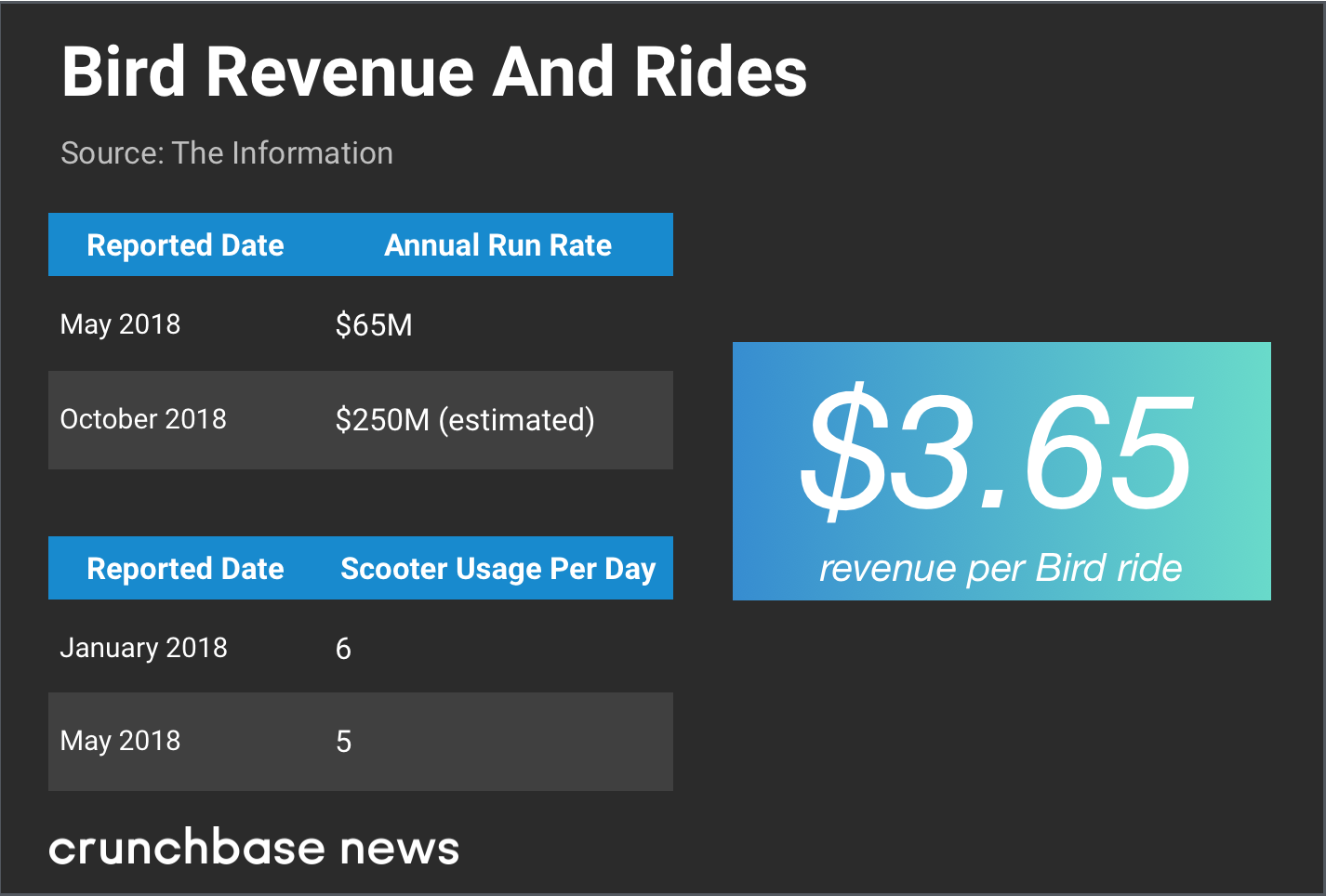

Bird generated $3.65 per ride, far above our estimate of $2.50. Bird scooters were handling six rides per day in January of this year, a figure that fell to five by May. The number of rides per day matters for Bird and other scooter companies. If they can generate more revenue per day per scooter by increasing utilization, their model makes more sense. Here we see the opposite trend.

Those rides grew Bird’s revenue from a run rate of $65 million 1 in May of 2018 to “hundreds of millions of dollars annually” by this October.2

So the company has growth figured out; however, its profitability is a different matter.

Gross Margins

As the above chart indicates, Bird has a diverse set of revenue costs. Let’s explore them.

Bird’s gross margin3 is 19 percent. That’s what left of revenue after charting (47 percent of revenue), repair (14 percent), credit card processing (11 percent), regulatory costs (5 percent), and customer support and insurance (3 percent).

Is 19 percent good? Not really. Keep in mind that a company has to pay its operational costs from its gross profit. Gross profit is revenue minus cost of revenue. So if you only have 19 percent gross margins, you’ve spent most of your revenue just generating your top line. At Bird’s old $65 million run rate, for example, the firm would only have $12.4 million left over after costs of revenue to pay for offices and staff with 19 percent gross margins.

Software companies sport gross margin percentages in the high 70s to low 80s. That’s why they are worth so much; their revenue is extremely profitable on a per-dollar basis.

The figures above tell us margin improvement (getting that gross margin percentage higher) at scooter companies will be paramount. At Bird’s current gross margins, the firm and its cohort will struggle to generate operating profits.4

The Information goes on to note that “Bird projected much better economics in the ‘near term,’ allowing it to generate a 33% gross profit margin.” I’d wager that’s the golden ticket. Every percent of gross margin that Bird can drive at the moment, holding revenue flat, raises its gross profit by around 5 percent. That’s enormous.

Thinking a bit more, Bird and Lime must be consuming mountains of cash (more here and here) for investing purposes; neither, given our math, generate anything like enough cash to finance their employee costs—let alone what they are spending on new hardware. So I’d hazard that while either firm is adding markets to their portfolio, they are working to add capital to their accounts.

And it’s still a damn fine time to do that.

Consider all the above a snapshot. More revenue metrics will leak, at least as long as the scooter world needs to raise cash. And then we’ll have an even more complete picture.

Top Image Credit: Li-Anne Dias.

Run rate, in this case, is the pace of revenue generation for Bird for a certain time period, annualized.↩

The takeaway here is that Bird grew rapidly in 2018 to nine figures in revenue.↩

Gross margin is the percent of revenue left over after cost of revenue is deducted from the firm’s revenue.↩

Operating profit is gross profit minus operating costs; if Bird can increase its gross margins, it has more gross profit with which to pay its operating bills.↩

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of stopwatch - AI [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Halftime-AI-1-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers