Nearly two years after special-purpose acquisition companies became cool, a slew of these blank-check companies are approaching their deadlines to find targets and merge.

In 2020, 248 SPACs went public, merging with companies like DraftKings and Virgin Galactic. While some were hits, many SPACs last year greatly underperformed.

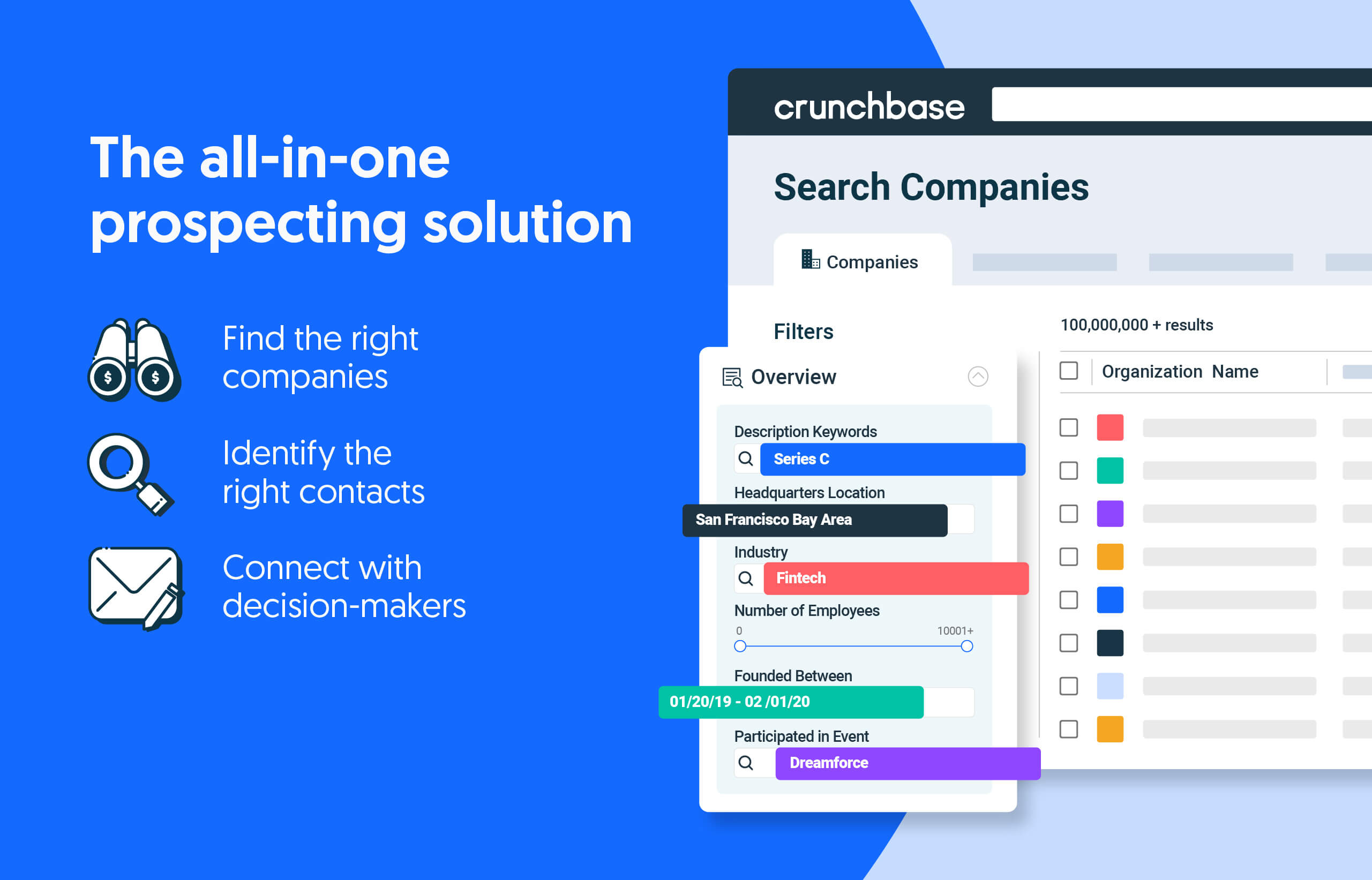

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

But with a stacked pipeline of SPACs searching for targets and a challenging macroeconomic environment that has largely stalled new public stock offerings, SPACs will have to hustle harder than ever to get deals done. Otherwise, they have to look at their options.

Get the deal done

SPACs that are approaching their deadlines have roughly four options, according to Louis Lehot, a partner at the law firm Foley & Lardner LLP.

The first, and best, option, is to enter into a letter of intent with a target company, essentially getting the ball rolling on a merger. Lehot said he’s noticed more SPACs hustling toward this goal, and more target companies requiring exclusivity agreements baked into letters of intent. That’s so that SPACs don’t turn around and instead pick a different company to merge with (many SPACs are pretty desperate to get to a letter of intent at this point, according to Lehot).

We’ll likely see SPACs attempt to get deals done as best they can because “a deal is better than no deal,” according to JR Lanis, vice chair of Polsinelli’s securities and corporate finance division.

Those deals may be more aggressive from the buy side, in other words the SPAC side, which could mean overpaying for an asset or “really looking under every stone and finding every possible option,” Lanis said.

‘Six-month safety valve’

The second option is to tap into the “six-month safety valve” that many SPACs have, Lehot said. Many SPACs allow for a six-month extension to the initial deadline–something that’s helpful if, say, there’s already a letter of intent with a target company and the SPAC just needs a bit more time to close the deal.

If a SPAC doesn’t have the option for a six-month extension or it’s already used that deferral up, there’s also the option of going to stockholders and asking them to amend the SPAC’s charter, Lehot said. That’s a pretty big hurdle, though, as it requires the same vote that a merger would need, according to Lehot.

There’s also the fact that many investors who may have had their money in the SPAC for more than a year at that point wouldn’t be eager to extend, according to Lanis.

“Especially in an inflationary environment with money becoming more expensive, you don’t want it just sitting there, you want it deployed,” he said.

Worst-case scenario: Liquidate

The worst-case scenario, and last option, is to liquidate the SPAC. In this situation, investors would get their money back, and the SPAC sponsor would lose money—usually around 2.5 percent to 5 percent of the trust value, according to Richard Humphrey of SPAC Research.

So far, there’s only been one SPAC liquidation this year, according to Humphrey, with Burgundy Technology opting to liquidate its trust.

Humphrey expects most SPACs will choose to extend if they can, or ask for that extension, but we’ll likely see more liquidations in the next three to 10 months. Currently, there are at least four SPAC charter extension meetings on the calendar this month, according to SPAC Research.

“I’d think we’ll definitely start to see more liquidations because there’s a ton of SPACs out there and they’re reaching the end of their runway,” Humphrey said.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of stopwatch - AI [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/Halftime-AI-1-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers