Next in the series we welcome James Currier, managing partner and co-founder of NFX. We talk network effects, how NFX moved away from an accelerator model, what’s wrong with Silicon Valley, why NFX is focused at the seed stage, and why he is currently not running a big, lasting, long-term company. The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Subscribe to the Crunchbase Daily

Gené: Welcome James Currier founder, angel investor turned into a fund manager with the founding of NFX fund in 2015. Why NFX?

James: We said let’s try to build a venture firm with network effects. We believe that the most interesting, most impactful things have big network effects. Originally we started with an accelerator. We dropped that two years ago. We were doing 15 companies per class. We either need to scale up to 80 per class, to get the random effect, to make that model work. Or we needed to scale down and increase the percentage ownership. In the end we decided to scale down and increase the percentage ownership and be a straight fund.

Gené: Why the name NFX?

James: It stands for network effects. What we realized in about 2010, is that all the companies we had invested in as angels, that we were really excited about, all had network effects. They were growing. They were defensible. Mostly about defensibility.

Gené: Given that we’re in the Internet era and everything’s connected, does almost every company have a network effect?

James: About 20 percent of the business plans have network effects in them, and 80 percent don’t. So if you’re a medical device, a synthetic biology company, SaaS software, enterprise software, or direct to consumer products, these things do not have network effects. These things have scale effects. They could have embedding effects, or they could have brand effects as their defensibility. But in the digital age, there are very few defensibilities left.

Gené: And why don’t they have network effects?

James: So the basic definition of a network effect is that every new user or new customer makes the product more valuable for every other customer. The first time we saw network effects was with telephones.

Gené: Which companies have stood out with a huge network effect?

James: Just look at the most valuable companies in the world. Microsoft is still one of the top market cap companies in the world, and they’ve been working on that two sided platform network effect since 1976. And then you’ve got Facebook, you’ve got Google, and you’ve got PayPal.

There’s like five or six of us who just spend so much time looking at this, Tom Eisenmann at Harvard Business School, Scott Cook from Intuit, and a few others. There’s actually some interesting what we call “social network effects,” but not social network. One of them is naming. So “let’s grab an Uber” is a real problem for Lyft right. “Google that” is a real problem for Bing, Once Google became a verb, that’s an incredible social lock. It’s just awkward for me to use Bing if you tell me to Google something. That’s right on the edge of brand. Brand is different or the bandwagon effect.

Gené: What other companies have a network effect?

James: Think of the big valuable companies, Uber, Lyft, and Slack. The more people in your company that use Slack the more valuable Slack becomes for you. Dropbox. Once my designer said, “Hey, I’m going to be sending you the mocks of the website on Dropbox”, and suddenly 76 people signed up in the next 48 hours because we had to get his mocks, all the engineers did and all product managers. Airbnb, the more properties, the more buyers. The more buyers the more properties. eBay, Amazon Marketplace. More than 50 percent of all transactions on Amazon are now going to the marketplace. They’ve basically taken over what eBay was 15 years ago. It’s a two sided marketplace network effect. IOS. If you look at Apple’s market cap. It was $42 billion. And then they added iMusic for sharing music. And then they added iOS. Those were their first two network effect products. And then their market cap went up by 10 or 15 times. Before that they were selling hardware and software.

Since 1994, since the Internet connected everything, we looked at the 336 companies which have become worth over a billion. We looked at each of their business models and said, “Did they have a network effect at the core?” And if they did we looked at the market cap. 70 percent of the market cap came from companies with network effects, 30 percent did not. Yet only 20 percent of the businesses had network effects in the business plans, and 80 percent did not. So that seemed like a huge imbalance. So that’s why we decided to do NFX in 2010 but we didn’t get around to it because I was still running Jiff.

Gené: What else are you trying to fix in venture?

James: We’re trying to help seed stage founders figure out how to navigate to their best investor. And that’s why we built Signal to find the best investor for you. We don’t take salaries. We use the management fee to hire engineers and staff to support the company. We are building a platform to help the ecosystem.

We build our own CRM, and data analysis. And we’ve got an internal group which helps with pitch development, which helps with PR, culture building, hiring. Within a few weeks we’ll just answer so many questions, so that the founders can get back to product and iterating.

Gené: Your most recent fund is $275 million, a pretty large seed fund, which you raised in April 2019?

James: We are a seed and pre-seed fund. Instead of investing over two years we’re going to invest over three years. We’re still going to be investing one to three million and lead seeds. In this fund we will make 35 investments. Four of them will be at a valuation which we would all consider to be a Series A, which is over $20 million. But we’ve also done probably 10 pre-seeds where we put in $250K, and help the company figure out what they want to do.

Gené: What are the valuations for pre-seed and seed rounds?

James: Valuations for pre-seeds are typically one million dollars pre-money. For a seed round I guess the average would be about eight or nine million dollars pre-money. Our sweet spot for seed is investing is about $1.5 million in a round.

Gené: How many companies do you meet in a year as a team?

James: We evaluate 3,000 companies a year, and then we’ll probably meet with 400. And invest in 15 companies in year.

Gené: You invest in the Bay Area and Israel. How do you help startups build a network effect?

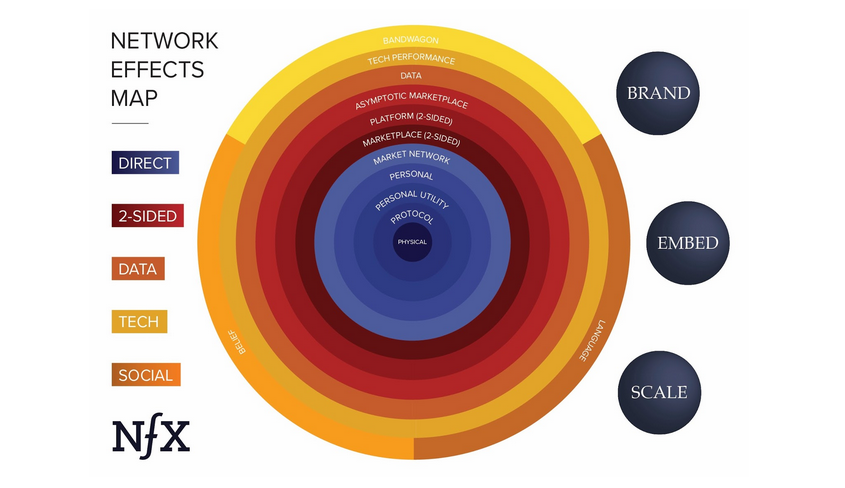

James: We’ve published this whole manual about the 13 different network effects. Starting with the physical, which is the telephone or Comcast in the middle. And then you go into weaker and weaker network effects as you go out.

Once you understand each of these, you can start to imagine how to add these network effects to the various businesses. Whoever adds a network effect first wins. Because it adds more value without you doing anything. Someone signs up and pays you money, and suddenly your product is more valuable for everyone else. We’ve written long articles about Facebook and their defensibility. They’re not going anywhere.

Gené: Facebook from what I understand worked hard to get each user 10 to 20 friends. Once you have that network you were never going to leave.

James: 10 for Facebook, 16 for Twitter, and 6 for Path. We call that network density

Gené: Path however was not successful?

James: They weren’t because they were too late and the other platforms were largely serving the needs of people. Facebook messenger is a personal utility, which is actually stronger than Facebook. I can make payments, my wife wants me to pick the kids up at school. I can’t leave. Whereas Facebook, I can turn off.

Interestingly enough, the reason I exited the companies that I have is because they didn’t have network effects…Because if you really want to make an impact in the world, the best way to do it is to run a network effects business like Nextdoor, or LinkedIn, or Tencent.

Stan, who’s a minor partner at an NFX, is now running Facebook Messenger. He and I have been talking about building the global currency since 2004 when I bought Blue.com with the intention of either building a spiritual group, or building a global currency.

I never got to do it, but he’s doing it as a part of Facebook. So once you get in a platform like that you have the opportunity to actually do these important things for the planet. Had I had a network effect business, I would not be a VC, I would be running that.

Gené: Given that you’re investing in such an early stage, how do you perceive growth focus in our industry.

James: So let me be clear. Network effects is about defensibility and retention. Viral effects are about growth. Network effects are not about growth. It is about retention. It is about keeping people in. Network effects reduce churn.

We also want companies to grow very quickly, because fast growing companies attract the best people. Fast growing companies have more opportunities to do more creative stuff. Fast growing companies means that they’ve hit on something important to somebody. That is different from the sugar-coated viral growth of 2004, that people think of as growth hacking. We were very good at that, at that time. We did a bunch of that between 1999 and 2007. We invented a lot of A/B testing methodologies, and a lot of the viral loops. But since Facebook shut down Facebook Platform, virality has gone to near zero across the digital world.

Gené: What is virality?

James: Virality is when a user of yours gets you another user for free.That was a 1998 to 2012 thing. It had a good 14 year period, and then it was over. But a very interesting period, with a lot of math, a lot of iteration.The culture of Silicon Valley, that we think of as Silicon Valley came from that age of rapid iteration, and changing all the time, and never sleeping. It was very exciting. It’s like running a 24 hour news program because things were changing so fast.

Gené: Viral still seems to be here for users recommending brands?

James: Yes, there are still incentivised as viral programs. If you get someone to try Lyft, I’ll give you 20 bucks. Those are very popular. But that’s not for free. And in fact, for most of those companies their cost of user acquisition to the channel is higher than just buying ads on Facebook. But they don’t want to stop it, because it makes so much sense. And it gets the users to attach their own brand to the brand of the company.

So what we talk about is more fundamental growth. And that has to do with the name of the company, what is this thing for people, how valuable is it compared to the alternative, how do you lower the barriers to friction for people to use it. These are fundamental growth issues as opposed to growth hacking.

Gené: So would you throw growth hacking out?

James: We do throw out growth hacking, except for the iterative culture that growth hacking bequeathed us. Because there was no A/B testing until about 1999. You can’t A/B test a shoe, or a computer, or a car. You put it out there. It works or it doesn’t. The mentality of A/B testing, the mentality of iteration, and letting go of what doesn’t work and trying something until it does, that we want to keep.

But the idea of creating very slick viral flows across the Facebook platform. Those days are gone. Even Upworthy, which was viral with their positive psychology stuff, which I loved, that’s dead now. Buzzfeed is dead.

There are fundamental growth principles that are very deep. Which means you gotta get the founders to change the name of the company. The old name, no-one can remember it. No-one can spell it. Every ad you put out there, you’re going to lose 40 percent of value, because no-one can remember the name.

We need a stronger voice in this community about the creative product culture that brought us here, originally, as the waves of money culture flow over us. And figuring out how to create a protected area for entrepreneurs and founders who care more about the product and customer than they do about money. It is just a switch. Money can be second. You need fuel to grow, to attract talent to build the product. But that’s not the goal. And if it’s money first and creative to get the money, that’s really different. It’s really sour.

Gené: Do you think Silicon Valley has gone that way?

James: If you’re writing a blog post and or tweet and you want someone to pay attention to it, you gotta put the numbers in. For instance, a lot of journalists say unless you have a financing they can’t really write about you. I think it’s because it’s the path of least resistance to aggregate confidence in something.

Gené: This whole ecosystem is becoming global. Do you think that’s a protection against this money first culture, or do you think that just travels from Silicon Valley.

James: I think it travels, because people perceive Silicon Valley through the eyes of the bloggers and journalists. And the people tweeting out. And what they are blogging about is the money, and who made what. Because that’s what people click on and read. So people outside understand if I go to Silicon Valley, I can make money. Silicon Valley is a product. People are incepting that I get money if I go there.

Gené: So how do you change that?

James: I don’t think we can stop that. But I think we can create a pocket of people, and language, and writing, and events like the lobby. And the stronger the community who wants to keep it about creativity, and about product; and the more of Silicon Valley we influence; the more the products will be influenced; the more of the rest of the world we influence to really go after the creative future, rather than ‘I made a lot more money than you and therefore I have more worth.’

Gené: What wave of technology are you riding?

James: We are riding synthetic biology. We are finding two-sided platform network effect businesses in the synthetic biology area where there’s three technologies which are all three on Moore’s Law sort of curves.

What is synthetic biology?

James: It’s essentially applying computation to the measurement and design of biology. You can do a lot more now, than you could because you have robotics, which are getting much cheaper, and are able to do 600,000 tests in an hour, versus six tests in five years. Machine learning, machine vision, and AI is getting better and better at processing and speed. Then the actual editing, the sequencing cost is coming down. Which is opening up vast new capabilities people haven’t even thought of. We are now waiting for the founders. There’s this gap between what the tech can do today, and what the founders are even thinking of doing, which is exactly where you want to invest.

Gené: This is for disease prevention?

James: For disease, agriculture, oil and gas, replacing palm oil, and impossible foods. It touches almost every industry. It is incredible.

The other thing we see happening right now is that there has been enough fintech infrastructures built on top of the old rails, so that it’s becoming easier and easier to build faster and faster fintech related companies, or fintech enabled marketplaces, fintech enabled brokerages. The ease of developing in the fintech area, through regulation is much easier than it was three or four years ago.

Gené: Is this due to platform players in the fintech?

Companies like Plaid that make it easier to get an API, or Stripe. So that’s another technology wave that we’re going with.

I feel as if the waves of tech change are slowing down compared to where they were in 1994 to 2012, because of TCP/IP and then because of mobile devices, opened up a huge Pandora’s box of potential. We haven’t had one of those big tectonic shifts since 2008. These are micro changes but the markets are so much bigger. Then the access is so much bigger. So the cost of acquisition is so much lower than it was in 1994 to 1998, because so many more people are on these networks and are easily addressable. So I think that’s making up for the fact that it’s not necessarily a tech wave. It’s a scale wave.

Gené: What are the two companies that you are excited by and why?

James: Ribbon based in New York is doing financial products in the real estate sector. They allow people to buy residential houses for cash. It’s a product that the agent can give to their buyer and then get the other agent to use the other side. So the network effect to new agents using Ribbon lowers the cost of house acquisition, and increases the amount of cash transactions.

So I go from saying I offer you $100k for your home and I’ll get a mortgage to saying I’m going to give you cash but I’ll give you $95k right now. And you say deal, done. And so Ribbon takes 2 percent. I as the buyer save 3 percent. You get the cash you want. The agent gets the transaction done. They each make their commission. Ribbon gives the cash for two to eight weeks for the transition to take place. And then the home buyer gets a mortgage. It really helps when you want to buy a home before you sell your other one. I can’t afford to buy a new home, until I sell my old home.

Another one would be Mammoth Bio Sciences, which is the largest repository of CRISPR IP in the world, which is gene editing. Jennifer Doudna, a co-founder is a discoverer of CRISPR. They’ve created a platform play, and then they’re working with pharma and agricultural companies to develop diagnostics and therapies to edit change in a responsible way. The more people use the platform, the fewer experiments everyone needs to do because things have already been checked off. And there’s just more data available.

Gené: Anything we did not cover?

James: We as founders have built 10 companies prior to starting NFX. Despite the money culture, we have exited for $10 billion. No other group has done that. It is about 2x any other new venture firm. As a venture firm of founders we’ve really been in the trenches for a while. I’ve made so many mistakes and have so much scar tissue. Let’s build a venture firm which is about building companies from the operators perspective who have been in their shoes. And that brings ethos, and respect, and authenticity to the conversation. That’s one thing that I think is important to us. We don’t dislike VCs who haven’t been operators. There are a lot of great VCs. But if I’m a founder, I want a founder.

Crunchbase links – NFX Portfolio Companies

Illustration: Li-Anne Dias.

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

67.1K Followers