Last week, gene editing startup Prime Medicine announced it will brave the unforgiving public market with a $175 million IPO. The company followed Third Harmonic’s $180 million August debut, making these companies two of only 25 biotech companies to enter the public markets this year.

Interestingly enough, neither Prime Medicine nor Third Harmonic went public with any strong clinical data, a key metric to getting funding in the private space. Clinical data shows proof of concept, which is usually the bare minimum most companies must have before they go public.

But biotech is a different beast. While most tech companies enter the market armed with millions in revenue, a strategy toward profitability, a solid capital expense, and strong projections for the long haul, few of the record 143 biotech startups that made their public debut last year had a product to sell.

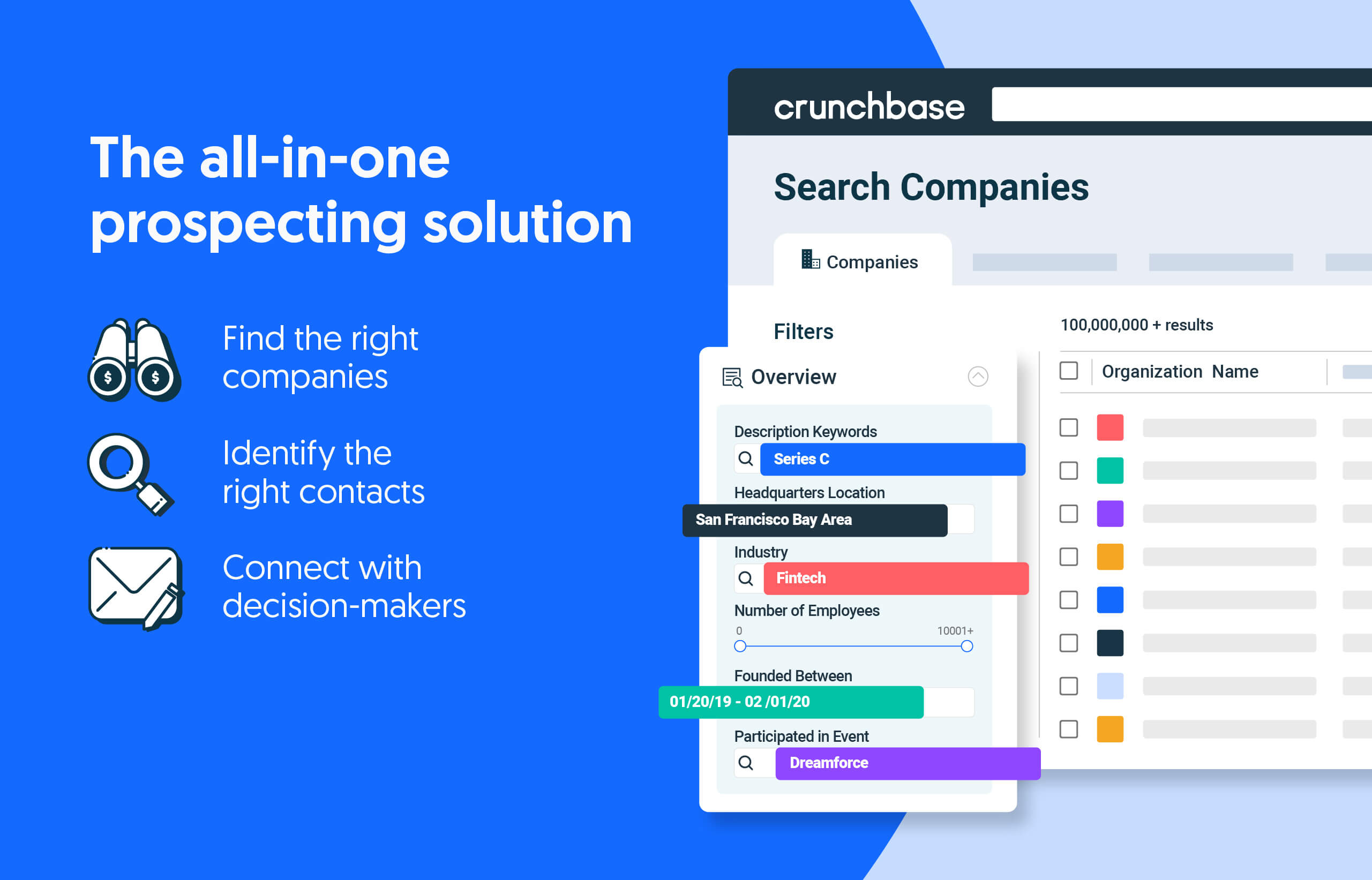

Search less. Close more.

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

Prime Medicine and Third Harmonic may be a sign that biotech IPO activity will start picking up soon. But what does that really say about the biotech market?

What’s the point of a biotech IPO?

“What’s unique, particularly around biotech, if you compare it to almost any other industry or segment, is going public as a biotechnology is merely a financing function,” said Heather Gates, an audit and assurance growth executive at Deloitte & Touche.

Indeed, there really isn’t a big difference between a biotech startup and an exited biotech company other than how much money they need. It takes about 10 years to make one drug, and in that process, there’s a 90% failure rate. The goal is to find funding where you can, when you can. And in 2021, IPOs were a great source of funding.

“It’s a pretty long cycle, 10 to 12 years on average,” Gates said. “So you kind of need to resort to other financing sources. And our markets have been open and receptive to that for many decades.”

Many biotech startups don’t seem like conventional IPO candidates. Nexgel, a hydrogel biotech company that went public at the end of last year, raised two seed rounds of less than $500,000 each before diving headfirst into the Nasdaq. The second seed round was raised in 2020. But the first? 2009.

There’s also the oncology-focused Cingulate Therapeutics, which raised $7.5 million in funding, didn’t make it to a Series A, and then went public in December last year. Despite a poor public market performance, it used the IPO to facilitate and publish promising early-stage data on an anxiety treatment.

And then there was the pandemic’s effect on funding for what used to be a rather overlooked, antiquated space in tech.

Timing is everything

But the public markets aren’t doing so hot now, which is bad news for IPO-ready biotech startups anyway.

Geopolitical sanctions and supply chain bottlenecks caused several of those fresh-on-the-market companies to crash, leading to more scrutiny in regulatory filings for newcomers. It’s the kind of low biotech hasn’t seen since 2010, when going public was a rarity for the industry.

This also means startups looking to generate cash via exiting aren’t going to get the dollars their predecessors acquired.

“Right now, I would not be thinking about doing an IPO for quite some time,” said David Crean, managing general partner at Cardiff Advisory. “I don’t think the market is really ripe for it to maximize your pricing in the IPO.”

M&A activity

The public market is a cruel, inhospitable ecosystem that ebbs and flows, but mergers and acquisitions, are forever — at least in biotech.

Most companies opine for a large pharmaceutical acquisition in their lifecycle (because nobody wants to be the next Pfizer).

And acquisition activity doesn’t look terrible. So far in 2022, there have been 91 deals to the tune of $11.8 billion, on par with acquisition activity between 2018 and 2021. Compared to IPOs, it seems like a far more reasonable bet that biotech companies will get acquired than go public.

Nonetheless, share prices in the public markets have dropped considerably, leading to lower valuations trickling down the pipeline. This may make investors more likely to engage with the biotech market and could lead (eventually) to more IPOs.

The cycle continues.

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

![Illustration of 50+ woman on smartphone. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Femtech_-300x168.jpg)

![Illustration of pandemic pet pampering. [Dom Guzman]](https://news.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Pets-2-300x168.jpg)

67.1K Followers